Legal Blog

Government Actions Against Law Firms - Status as of April 14, 2025

A summary of the government actions against law firms, including responses by law firms and the status of lawsuits

There’s a lot going on in terms of the public governmental actions involving law firms, so here’s a summary as of April 14 to help keep track.

The White House has issued broad executive orders targeting six Big Law firms, alleging misconduct, discriminatory practices, and misuse of firms’ pro bono practices.

Four of the six firms have filed lawsuits challenging parts of the executive orders in D.C. District Court. Three judges so far have issued temporary restraining orders that stayed parts of the EOs issued against Perkins Coie, Jenner & Block, WilmerHale. Susman Godfrey filed its lawsuit on April 11 and did not request a TRO that day.

Of the two firms that have not filed lawsuits:

one (Paul Weiss) reached an agreement with the White House.

The other (Covington & Burling) was the subject of a limited executive order and has not filed a lawsuit or reached an agreement with the White House.

Multiple amicus briefs have been filed in support of Perkins Coie, Jenner & Block, and WilmerHale, including a group of 507 firms that joined an April 4 amicus brief led by Munger Tolles & Olsen and Eimer Stahl and a larger group of 808 firms that joined similar amicus briefs filed on April 11 (note: my practice was one of many solo practices that joined the briefs).

The executive orders do not allege specific crimes by the firms, but cite conduct relating to investigations of President Trump, the January 6, 2021 Capitol incident, work on elections, abuses of firms’ pro bono practices, and discriminatory hiring practices. Some executive orders specifically mention the hiring of people who had investigated President Trump.

Eight big firms have reached agreements with the White House to avoid sanctions. Skadden, Milbank, Willkie Farr, Kirkland & Ellis, Latham & Watkins, Simpson Thacher & Bartlett, A&O Shearman Sterling, and Cadwalader, Wickersham & Taft reportedly reached agreements with the White House without being sanctioned in an executive order.

The Equal Employment Opportunities Commission’s Acting Chair sent letters on March 17 to 20 law firms requesting information about their DEI-related employment practices. On April 11, the EEOC announced settlements with four firms - Kirkland & Ellis, Latham & Watkins, Simpson Thacher & Bartlett, and A&O Shearman Sterling.

Overall, many of the biggest firms in the country have not taken public positions regarding the executive orders. Arnold & Porter, Crowell & Moring, Davis Wright Tremaine, and Fenwick & West have joined the amicus briefs, even without being targeted in an executive order. Two big firms are representing the firms in two other lawsuits - Cooley is representing Jenner, and Williams & Connolly is representing Perkins and joined the amicus briefs. (see the image for more)

The White House also issued a memorandum on March 22 directing the Attorney General to seek sanctions against attorneys who engage in “frivolous, unreasonable, and vexatious litigation” against the United States. The memo also accused the Elias Law Group's founder of misconduct, based on his prior work at Perkins Coie.

Sources and links:

Feb 25 EO re Covington & Burling https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/2025/02/suspension-of-security-clearances-and-evaluation-of-government-contracts/ (this EO specifically mentions the work done by some people to assist Special Counsel Jack Smith during his investigation)

March 6 EO against Perkins https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/2025/03/addressing-risks-from-perkins-coie-llp/ (this EO specifically alleges that the firm “undermin[e]s democratic elections, the integrity of our courts, and honest law enforcement,” and cites the firm’s work on elections) and Perkins’ response https://www.perkinscoiefacts.com/

March 14 EO against Paul Weiss https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/2025/03/addressing-risks-from-paul-weiss/ (this EO specifically mentions a 2021 pro bono lawsuit brought on behalf of the District of Columbia Attorney General relating to the January 6, 2021 Capitol incident) and March 21 EO regarding “remedial action” https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/2025/03/addressing-remedial-action-by-paul-weiss/

March 17 EEOC release regarding 20 law firms https://www.eeoc.gov/newsroom/eeoc-acting-chair-andrea-lucas-sends-letters-20-law-firms-requesting-information-about-dei and April 13 release about four settlements https://www.eeoc.gov/newsroom/eeoc-settlement-four-biglaw-firms-disavow-dei-and-affirm-their-commitment-merit-based

March 22 presidential memo “Preventing Abuses of the Legal System and the Federal Court” https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/2025/03/preventing-abuses-of-the-legal-system-and-the-federal-court/ and the Elias Law Group’s response https://www.elias.law/newsroom/press-releases/statement-from-elias-law-group-chair-marc-elias

March 25 EO against Jenner & Block https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/2025/03/addressing-risks-from-jenner-block/ (this EO alleges that the firm “engages in obvious partisan representations to achieve political ends, supports attacks against women and children based on a refusal to accept the biological reality of sex, and backs the obstruction of efforts to prevent illegal aliens from committing horrific crimes and trafficking deadly drugs within our borders”) and Jenner’s response site https://www.jennerfirm.com/

March 27 EO against WilmerHale https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/2025/03/addressing-risks-from-wilmerhale/ (this EO alleges that the firm “engages in obvious partisan representations to achieve political ends, supports efforts to discriminate on the basis of race, backs the obstruction of efforts to prevent illegal aliens from committing horrific crimes and trafficking deadly drugs within our borders, and furthers the degradation of the quality of American elections, including by supporting efforts designed to enable noncitizens to vote”)

April 9 EO against Susman Godfrey: https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/2025/04/addressing-risks-from-susman-godfrey/ (this EO alleges that the firm “spearheads efforts to weaponize the American legal system and degrade the quality of American elections” and funds groups to “undermine the effectiveness of the United States military”) and Susman’s response https://www.susmangodfrey.com/news/susman-godfreys-statement-in-response-to-administrations-executive-order/

Many bar associations, including the American Bar Association, have issued statements criticizing the governmental actions. Some are collected at https://www.americanbar.org/groups/bar-leadership/resources/resourcepages/executiveorders/

Amicus brief by 504 law firms https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/67cf71f1f27ef68a8f5c5c70/67f3f782437ea8038058313e_LawFirmsAmicus-v2.pdf and subsequent amicus brief by 807 firms https://static1.squarespace.com/static/67d4400d37a2b91e3aba58d5/t/67f97c475572271a0b04c89b/1744403528311/0045-001.+%2804-11-2025%29+807+LAW+FIRMS.pdf

Anatomy of a Civil Trial

A real-life civil trial, examined and discussed by a former federal prosecutor and two college students. Great opportunity to get a better understanding about how a civil trial actually works.

Every lawyer has to start somewhere, and I learned a lot by observing three criminal trials during and immediately after law school. So, when I hosted two college students for a one-week externship in March 2025, I took them on a tour of the federal courthouse, and we happened to see that a civil trial was about to start that very day. My externs ended up watching most of the trial, and we had great conversations every day about what they had seen and observed.

Yolanda Wang, Arrow Zhang, and I thought our discussions might be a useful way for other students to get a better sense of civil trials, so we recorded a discussion and are sharing it online. Hope you enjoy!

A few things for students to keep in mind:

This is a real-life case involving real people. Everything that Yolanda and Arrow saw was public, but we’ve not used the people’s names to protect their privacy anyways. If you want to look up the real case, contact me.

Civil cases are ultimately about two issues – liability and damages. When a plaintiff sues someone, they usually claim that the defendant did something wrong and that they suffered some kind of damages from that wrongful action. Ultimately, civil cases are often about money. How much should a defendant pay to resolve the case? In this case, there clearly was a mistake, but the big question probably was how much money the plaintiffs should get as a result.

In law school, you primarily will learn about legal arguments primarily through reading judicial decisions. But in real life, most legal work is about determining what really happened, which involves investigative skills such as interviewing, reconstructing what happened, and being able to communicate this to strangers. If you’re interested in being a lawyer, I highly recommend that you interview people, whether it be as a journalist, as an academic, or as some type of analyst.

Go to court yourself! Most trials will be interesting if you take the time to really observe them. Many federal courts have daily calendars online so you can see what’s scheduled. Pick a day when there are a few things going on and just go see what’s happening! And then, if you stick around long enough, introduce yourself to some of the lawyers when there is a lull in the trial. They probably will be wondering who you are, and many probably will be happy to talk with you. They had to start somewhere too!

Thanks to the Asian American Cultural Center for arranging this externship. Please contact me if you’re interested in setting up similar externship programs. I’m happy to help students and new lawyers get started!

How I Use Technology in My Trials

Some thoughts about how a former federal prosecutor uses technology to prepare for and conduct trials.

Just finished working in February 2025 on two trials, including one where the judge said that he was “in awe” of how the lawyers presented their cases, so I thought I’d share some general thoughts about technology in trials.

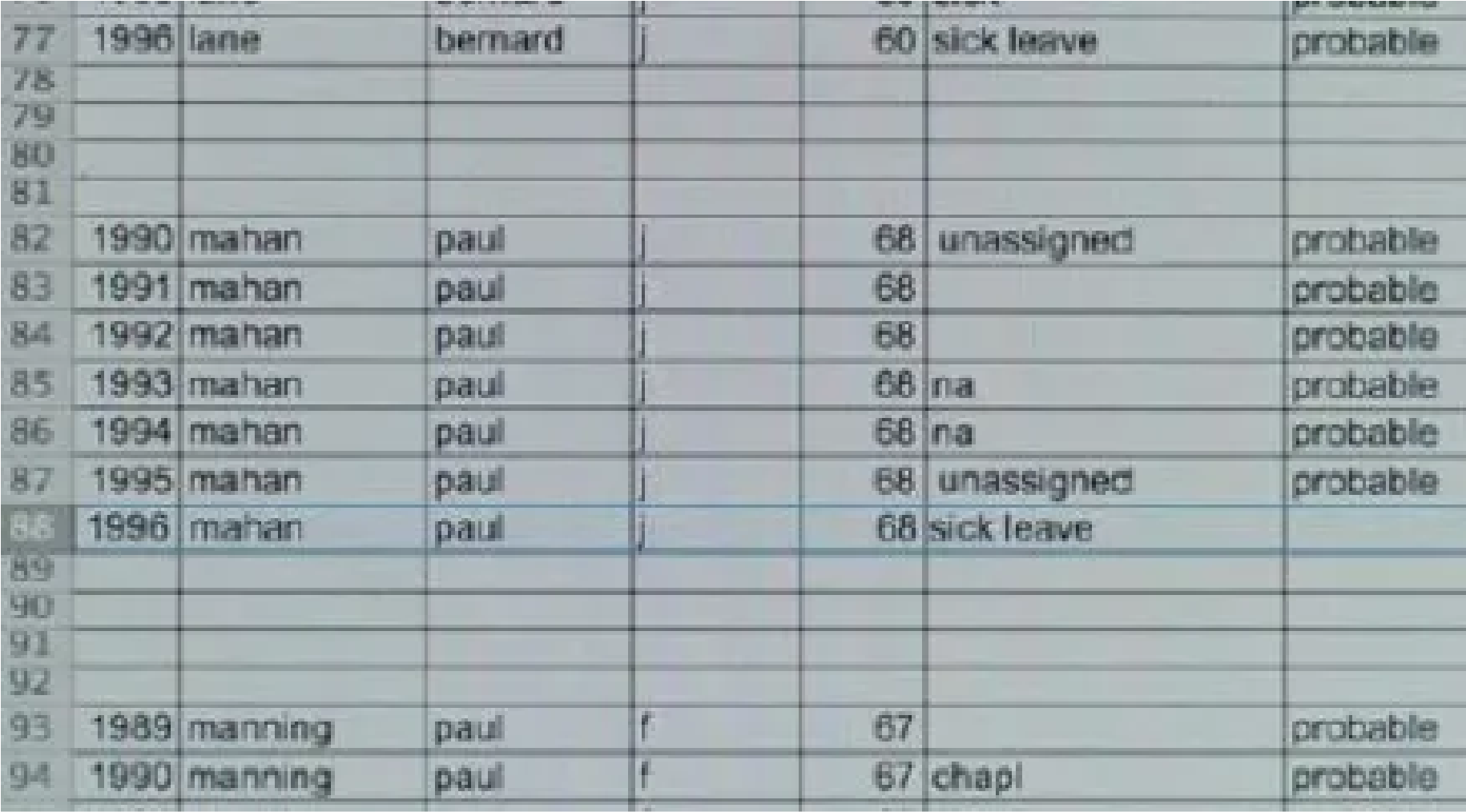

First, organizing information before trial is essential, especially because the discovery rules in criminal cases are so vague that the government often provides exhibits, summary charts, and new witness information during trial. I use Everlaw to organize discovery and exhibits, along with multiple spreadsheets, chronologies, and memos. With Everlaw, I tag documents in multiple ways, I use my own “date for sorting” field to reconcile inconsistent metadata, and I run searches sometimes even as witnesses are testifying to test new ideas. This helped me prepare from scratch for two back-to-back trials within just a few months.

Second, many lawyers rely on a legal assistant to display documents during trial (e.g., “Mr. or Ms. So-and-So, please display Exhibit 10 and highlight the second paragraph from the top”) – I do not. I use OnCue Technology to present exhibits myself. This makes the trial presentation more efficient, and it makes me think more in advance of exactly how I’ll present information during trial.

Third, I’m probably one of the few lawyers who regularly uses Excel during my witness examinations and who has taught juries how to use Excel. This has been helpful in several cases to make points that otherwise might be difficult to see or get. If you don’t know how to use Excel, you may be leaving evidence on the table.

Fourth, I so far have used AI in my cases for only one thing – generating rough transcripts of audio recordings for review purposes. This has been extremely useful and has saved lots of time. I’ve used Everlaw’s rough transcripts in two trials to identify key points for cross-examining witnesses, and I’ve then used the recordings themselves at trial.

Fifth, I generally take notes by hand using the reMarkable writing tablet. This helps me process the information in real time, more so than if I was merely transcribing on my computer what is said, and I can still review my notes on my computer or phone. I remember one trial where the government lawyers took no notes because they were relying on the transcripts that they got each night – I caution against this (and it's very expensive). If nothing else, taking notes helps signal to jurors that they should be taking notes too!

Sixth, I prepare my closings in PowerPoint, not Word. This helps me think about what the jury sees and hears throughout my argument, and I think it helps me engage with jurors because I have a core idea and maybe some key phrases for each slide, but I don’t have a script that I might be tempted to read from. I also design and run my slides myself so that I can adjust them and even make new slides as I listen to the other side’s argument.

Hope this helps!

(Photos are from the Northern District of Illinois website)

Data for Defense Lawyers

Long before Big Data and discovery dumps, courts warned about the danger of “trial by charts.”

In 1954, the Supreme Court warned that “bare figures have a way of acquiring an existence of their own, independent of the evidence which gave rise to them.” Holland v. United States, 348 U.S. 121, 128 (1954).The Fifth Circuit warned around the same time that district courts have “grave responsibilities” to ensure that a defendant is “not unjustly convicted in a ‘trial by charts,’ however impressive the array produced.” Lloyd v. United States, 226 F.2d 9, 17 (5th Cir. 1955).

Now, more than ever, defense lawyers should guard against the improper use of data and summary charts by the government. Moreover, they should also look for ways to turn this around on the government by looking for errors and sloppiness in the government’s analysis and by finding information in the data that they can use themselves.

I. Applicable Rules

There are a few rules to keep in mind when it comes to data analysis and summary charts.

Federal Rule of Evidence 1006 allows a party to use a “summary, chart or calculation” to “prove the content of voluminous writings” that “cannot be conveniently examined in court.” Courts have warned that summary charts are to be used with caution due to their potential for abuse. See, e.g., United States v. Norton, 867 F.2d 1354, 1362 (11th Cir. 1989) (“We recognize the caution with which these summaries are to be utilized, given the possibilities for abuse,” and finding that there was no abuse of discretion in admitting a chart when the chart’s assumptions were “amply supported by the evidence presented to the jury,” when the witness who prepared the chart testified and explained that chart, and when the defense conducted a “thorough cross-examination of the witness” and had “the opportunity to present its own version of those matters,” and when a jury instruction was given)).

A Rule 1006 summary should be a “surrogate” for voluminous records and must be an “objective accurate summarization of the underlying documents, not a skewed selection of some of the documents” to further one side’s theory of the case. United States v. Oloyede, 933 F.3d 302, 310 (4th Cir. 2019) (finding that government charts did not comport with Rule 1006 because of their selectivity).

Also, starting December 2024, Federal Rule of Evidence 107 will authorize a court to allow the use of "an illustrative aid to help the trier of fact understand the evidence or argument." Think about flowcharts and diagrams that might summarize information that is not necessarily "voluminous" but might help visual learners. Such charts also could have been allowed previously under Rule 611(a), which allows a party to use demonstrative charts to facilitate the presentation and comprehension of evidence already in the record.

The distinction between the rules can affect how the evidence comes in and what the jury can take back with them into deliberations. Charts that are admitted under Rule 1006 can be admitted as evidence, charts that are admitted under Rule 107 are typically demonstratives but can be allowed as evidence if all parties consent or if a court orders for good cause, and charts that are used under Rule 611(a) are only demonstratives.

If the government plans to use summary charts at trial, defense lawyers should consider working out a schedule for receiving draft charts so that they will have adequate time to review the charts before trial. Also, defense counsel should consider asking the government to identify the person who prepared the chart and consider asking questions about methodology.

Here are some things to consider:

Are the charts based solely on mathematical computations? If so, the chart is more likely to be admissible.

What assumptions were used to prepare the chart? Charts need not be “free from reliance on any assumptions,” but such assumptions must be “supported by evidence in the record.” United States v. Diez, 515 F.2d 892, 905 (5th Cir. 1975) (finding no error in government’s use of chart when the government’s assumptions were “amply supported by evidence already presented to the jury”).

Are the underlying records accurate, reliable, and admissible? Summaries of records are only admissible if the underlying records are otherwise admissible. Consider hearsay objections and point out ways that the records may not be admissible. For example, using bank records rather than accounting records may be better, as accounting records incorporate hearsay that may not be admissible. United States v. Batio, 2023 WL 8446388 (7th Cir. 2023) (Quickbooks records effectively put in the defendant’s characterizations of the financial transactions. Underlying records should have been used.).

Have all the underlying records been made available? Charts should be clearly sourced to other exhibits or discovery. If something has not been sourced, this can be a huge red flag. This is especially important now when data may be summarized from a live database at a particular time, making it impossible to reconstruct later exactly what records were summarized.

Are the underlying records being admitted into evidence? Rule 1006 does not require that the underlying records be admitted, but requesting that the underlying records be admitted is generally better. This way, defense counsel can use the underlying records to point out errors in the government's analysis and to make points that the government may not have anticipated.

Do the charts contain “conclusory captions”? If so, the chart is less likely to be admissible under Rule 1006. A witness may be able to testify about such conclusions, but there is a “danger in permitting the unrestricted use of such phrases upon charts” given “a jury’s natural tendency to accept such unsworn, conclusionary verbiage as authentic, primary proof.” Lloyd, 226 F.2d at 17.

Given all this, request summary charts well before trial, particularly in complex cases where the analysis may take a while. Analyzing these charts can give the lawyer insights into what the government is planning to do at trial, which can open up ways to attack or undercut the government’s case.

II. Think of Data Like a Witness

The government regularly dumps spreadsheets and financial records in the course of discovery, and the government itself often has not done a good job analyzing and understanding this information. But all this data can be very useful for defense lawyers and should be considered as part of overall case development and strategy.

Think of the data as a witness who the defense team can interview at length, who cannot be impeached, who can help impeach the government’s witnesses, and who might remember things that counsel’s client has forgotten or never even knew. It may take a lot of time and work to debrief that “witness,” but the data can help the defense present the client’s story and corroborate the defense in ways that the government may not even anticipate.

A big part of analyzing data is thinking about what questions data can help answer. Use questions like the ones below to help figure out if there are errors, sloppiness, and assumptions in the government’s case, just like counsel would review the interview reports that are the traditional part of discovery.

Does the data corroborate what the government’s witnesses or what the defense witnesses say? If what the witnesses say matches the data, then the witnesses have more credibility. But if what the witnesses say does not match the data, then the witnesses do not really know what they are talking about or are lying. The government’s lawyers should be checking this, but they sometimes take witnesses at face value.

In one of my cases, the government had multiple witnesses testify about alleged “patterns” of tests that a doctor always ordered. But the government had not checked this against the data, which showed that most of those tests were never billed. Either the witnesses did not know what they were talking about, or the doctor was performing tests for free. In another case, the government had a witness testify about some significant conversations but failed to check that witness’s story against the phone records. Those records showed that there was at least one significant call within the key time frame that the witness had not explained and could not recall, and they showed that another significant call might not even have happened.

Does the data show the proper context for the government’s claims? The government likes to use big numbers, but those numbers can be broken down and picked apart. How much money is really at stake? A large amount of money might support knowledge and criminal intent, but if the money at issue is a small percentage of total payments or income, it might be more likely to suggest errors and mistakes.

Does the data show improper cherry-picking? The government probably has chosen specific examples that it thinks are strong and powerful, but defense counsel should check if they are really representative of the alleged scheme. The data can help show that the government’s examples are more complicated than the government thinks, or that the government’s examples are one-off instances that are not indicative of the overall practice.

One of the best examples of countering improper cherry-picking in recent years happened in a case of constitutional interpretation involving the Emoluments Clause. During the Trump administration, the Department of Justice tried to argue for its interpretation of “emolument” in part by cherry-picking a few dictionaries from the 1600s and 1700s that were in its favor. Rather than just cherry-picking a few counter examples from other dictionaries, the lawyers arguing against the DOJ presented the judge with a full survey of every dictionary they could find. The overall data analysis showed that the Trump administration’s argument was in the minority, and the judge cited this in part in ruling against the Department of Justice. District of Columbia v. Trump, 315 F. Supp. 3d 875, 889-92 (D. Md. 2018).

Does the data show that there is more to the story than the government alleges? One big challenge from the defense perspective is overcoming a psychological bias that Daniel Kahneman has called assuming “what you see is all there is.” The government wants to present a simple story of fraud, but the data can show variation and complexity that the government and its witnesses may not be able to explain, and that may help sow doubt among jurors.

Did the government get something wrong in the indictment? Check the wires or the submission dates and see if there is anything that the defense can use to undercut the government’s credibility. In a healthcare fraud case, the defense discovered almost immediately that the government had misread its own data, confusing the submission date for each healthcare fraud count with the date of service. The government did not realize the error until halfway through trial, which was too late to fix the indictment and avoid some embarrassing testimony.

III. How to Review Data

One of the big obstacles for using data in a defense case is simply that many lawyers lack experience with it. Lawyers often joke about how they chose the legal profession because they were not good at math, but the evidence for many white collar crimes is in the spreadsheets and data the government provides or lawyers develop themselves. This is the era of big data, and not looking at data is leaving potential evidence on the table.

At its core, data analysis can help defense lawyers see things that otherwise would be invisible or difficult to see if they were looking at pieces of evidence individually or in isolation. Three general approaches will help the defense team analyze data: (1) show the denominator, (2) compare and contrast something, and (3) track something over time.

Show the Denominator

In white collar cases, the government will try to show that something happened multiple times, trying to convince members of the jury that something happened so many times that they should infer a pattern or bad intent. But what is the denominator? What is the government’s number a percentage of? Numbers should always be placed into context, and calculating the percentage is a key step in this regard.

In a healthcare fraud case, the government tried to show that the defendant had performed a few hundred operations that were improper according to an expert and that the operations were not randomly selected. Even if the government was right about the merits of the operations (it was not), these operations represented less than one percent of his total operations and were not meaningful when viewed in context.

2. Compare and Contrast Something

Another approach is to compare one data set to another to determine if similarities exist. In a case involving the Anti-Kickback Statute, the government cooperating witness testified that there was an agreement to be paid on a per-patient basis. During cross-examination, defense counsel showed the witness the government’s own data indicating the number of patients that were billed to Medicare on a monthly basis. Defense counsel did the math with him for each month, and the data showed that there never was a month even close to matching the details of his testimony. Even the government’s case agent conceded on cross-examination afterwards that defense counsel’s “Excel class” had shown that there was no agreement to be paid on a per-patient basis.

3. Track Something Over Time

The government might be focused on a particular event or transaction, but what happened before or after might provide useful context. In a recent case, the government used one set of records to show a high number of refunds that should have been made. But defense counsel focused on the process and showed that the government’s extensive analysis was based on records that the defendant did not have and had no reason to look for. He was given a different set of records, and those records showed a lower number of refunds that he thought was better than the industry average.

In another case, where the government focused on one type of medical operation, the defense showed that the defendant had done many precursor operations without doing the type of operation on which the government had focused. This showing undercut the government’s suggestion that the defendant did both types of operations with criminal intent.

Defense lawyers should think about how this can be done with anything that they get in discovery. It may be possible to pull data out of the discovery they have been given. If the government interviewed employees, track when those employees worked for the company and determine if there are key time periods that are not covered. If the government is giving counsel patient files all signed on the same day, counsel should check the time stamps to see if that helps provide context.

Even criminal records can be data. One famous use of data in a criminal case was cited by Yale professor Edward Tufte as a great example of data presentation. The defense attorneys in the case made a demonstrative chart tracking all the crimes that the government’s cooperating witnesses had been convicted of. The jury even requested a copy of this chart during deliberations and then acquitted the defendant.

If new lawyers and law students do not know how to use Microsoft Excel or similar spreadsheets, they should take a class or seek instruction from friends or colleagues. Knowing how to read and analyze a spreadsheet is a valuable skill for any complex litigation, but this is a skill many lawyers do not have.

Here are a few tools that can help counsel focus or identify the important data.

The “hide” function. Spreadsheets provided by the government often have more columns than can be seen on a screen or that can be printed out in a legible manner. Use the “hide” function to take out columns that are not significant to the relevant analysis.

The “filter” function. Spreadsheets often will contain hundreds or thousands of rows of data. How can counsel focus on particular aspects of the data? Use the filter function to show only specific rows, such as the rows associated with a particular date or person. For example, using filter can help counsel focus on the transactions or people associated with a particular count of the indictment.

The “sort” function. Every spreadsheet will come to counsel sorted in some way that may have made sense when the data was created or last saved, but counsel can sort it other ways. Use the sort function to put the data into chronological order, in order by amount of money, or in some other way.

The “page format” function. When printing spreadsheets, one should adjust the settings so that the printouts are more legible. First, go to “Page Setup” and change the “orientation” to “landscape” and change the “scaling” to “fit to” 1 page wide while leaving the “tall” pages blank. Second, change the “sheet” to repeat “$1:$1,” which will result in Excel printing the column headers on every page. Third, hide all columns that are not significant. These steps will result in a spreadsheet that can be printed out and reviewed.

Much can be done with Pivot tables and formulas, including having the computer analyze the data. Here are two things that can be done by tech-savvy defense counsel or someone else on the defense team:

Count how many times something appears in the data. How many times did a particular type of transaction occur? In a healthcare fraud case, how many times did the doctor bill for a particular billing code? The “countifs” function lets the user do that.

Add up something. How much money did a particular person receive? How much money was associated with a particular billing code in a healthcare fraud case? The “sumifs” function lets the user do that.

Lawyers can use these formulas to ask questions of the data, just like they would ask questions of a witness.

Start with the counts in the indictment. If the government has picked a particular victim or patient, look at all the transactions involving that victim or patient. If the government has picked a particular day, look at everything that occurred that day. If the government has picked a particular billing code, look at how that billing code compares with other billing codes.

With healthcare fraud cases, one approach is to start by making three lists using the “sumifs” and “countifs” functions, but the same thing can be done with pivot tables. First, one can create a patient list to help figure out how the government chose the patients cited in the indictment and if there are patients whom counsel can use to undercut the government’s case. Second, one can make a list of billing codes to help put the government’s allegations into perspective against the overall practice. Finally, create a list that tracks payments by month so counsel can see if there are any particular points in time that could be significant, such as a shift in billing that might reflect a conversation. These lists can help counsel get a better sense of the client’s practice and sometimes help counsel come up with leads to investigate further.

IV. How to Present Data

The government’s presentation of data in trials is typically very simple. A witness looks at a disc or a USB drive, confirms that he or she reviewed it before trial and that there are big spreadsheets on it, and the government moves to admit the disc or USB drive into evidence. And then the government moves immediately to the summary charts that make a few points based on the data.

Whenever the government does this, witnesses leave themselves open to a cross-examination that goes into the nuances of the data and shows that there is more going on. Has the government glossed over things? Has the government made bad assumptions? This is defense counsel’s opportunity to show it.

First, find something in the data that the government has glossed over or has not explained, and show this to the jury on cross-examination. Open those spreadsheets that the government admitted into evidence but did not show the jury. If defense counsel is lucky or the government has been sloppy (or both), defense counsel will be able to point out information in the government’s exhibits that undercuts the government’s case.

Second, defense counsel should use the government’s own witnesses to make some of the points the defense identified from its data analysis. The government’s data custodians just testified that they reviewed the data before trial and that they created summary charts for the government. Start filtering and sorting and hiding, and make those witnesses read into the record some facts that are good for the defendant.

Third, defense counsel may want to have a witness create summary charts that can be admitted via Rule 1006 and that make points which require more than filtering and sorting. These summary charts can also be helpful for jurors, who often use visual aids to help understand complex points and see things for themselves.

Rule 1006 generally requires a witness to have personally done the summary before court, but the witness does not need to have been the first person to do so. Defense lawyers should consider doing multiple types of analysis themselves and figure out which few are really important for trial. After this step, counsel can work with a witness who recreates the specific analysis that matters and can authenticate a chart that sometimes the witness and defense counsel create together.

The advantage of a summary chart under Rule 1006 is that it gives the jury something concrete that they can take with them into jury deliberations. The disadvantage is that it gives the government something to pick apart and spin.

On defense, it often is good enough to make a general point without getting bogged down in specifics. The government’s job is to do and present a thorough investigation, and the defense lawyer can communicate problems with the government’s case in a comprehensible manner without providing the definitive answers that the government should have provided. In one case, a witness conducted a thorough analysis, but the high-level summary was good enough to inform defense counsel’s cross-examination of the government witnesses and raise weaknesses in the government’s case. Had defense counsel created a summary chart, he might have had to turn it over well before trial, and the government might have fixed some of the problems or dropped some of its arguments. Using the data to inform the cross-examination of the government’s witness and to set up a short direct examination of the defense witness was good enough.

V. How to Get Data

The defense team should not rely only on the data that the government thinks is relevant. Prosecutors may have dumped massive amounts of data on the defense, but that is just the data they thought was useful or might have been useful to them. If they conducted a sloppy investigation, they probably did not collect or analyze data that might be useful to the defendant.

Catalog the data the government provided, and then consider what is missing.

Did prosecutors obtain all the relevant bank accounts? They may have missed accounts that fill in gaps in the government’s theory. Defense counsel can check with the client for missing bank account records, and counsel can issue subpoenas for those records.

Did they collect data for the right time frame? They may have collected data at an early stage in the investigation and did not think to update the data as the investigation continued.

Did they get data that puts the data into context? The government’s lawyers may have gotten data showing all of the client’s transactions with a particular person, but they may not have gotten data showing that person’s transactions with other people.

All this is particularly important in healthcare fraud cases, which involve a data-rich environment. The Department of Justice has real-time access to Medicare claims data, and it can get data from Medicare, Medicaid, and private insurers relatively easily. If a lawyer is representing a healthcare provider, the provider should have access to all the claims the provider submitted. And defense counsel has access to some publicly available databases that show aggregate information on what was billed to Medicare.

For years, Medicare has made available aggregate data for Medicare providers, such as data summing up what services a provider billed to Medicare. One link is at https://data.cms.gov/tools/medicare-physician-other-practitioner-look-up-tool. As of 2024, this data goes back to 2013 and is updated periodically. For a client in a healthcare fraud case, this data may help counsel see things about the client’s practice that he or she may not even know.

Defense lawyers can download the data themselves from the Medicare website, or they can take advantage of the work of some journalists who have made the data available in a more user-friendly format. The news organization Pro Publica has made the data for 2013 through 2015 available at https://projects.propublica.org/treatment/, and the Wall Street Journal did its own analysis at Medicare Unmasked (https://graphics.wsj.com/medicare-billing/).

Many doctors and medical professionals do not realize how much of their data is available and can be analyzed. There are doctors and medical professionals who have been charged and convicted of crimes, and it is possible they could have avoided prosecution if they knew what that data showed. Lawyers who have clients facing an investigation should check this data.

In all cases, defense counsel should consider requesting additional data to fill in the holes in the government’s data collection.

First, consider asking the government to produce materials under Brady or 3500. If the government has data, it may just give counsel the data itself.

Second, file a motion requesting such data.

Third, issue a Rule 17(c) subpoena. In a healthcare fraud case, check the government’s production to see which Medicare contractor provided the government with the data the defense wants, and then subpoena that contractor for the data.

Do not assume that what the government collected is all that matters or is all that exists. More data can help, just like more witnesses can help.

VI. Peer Comparisons

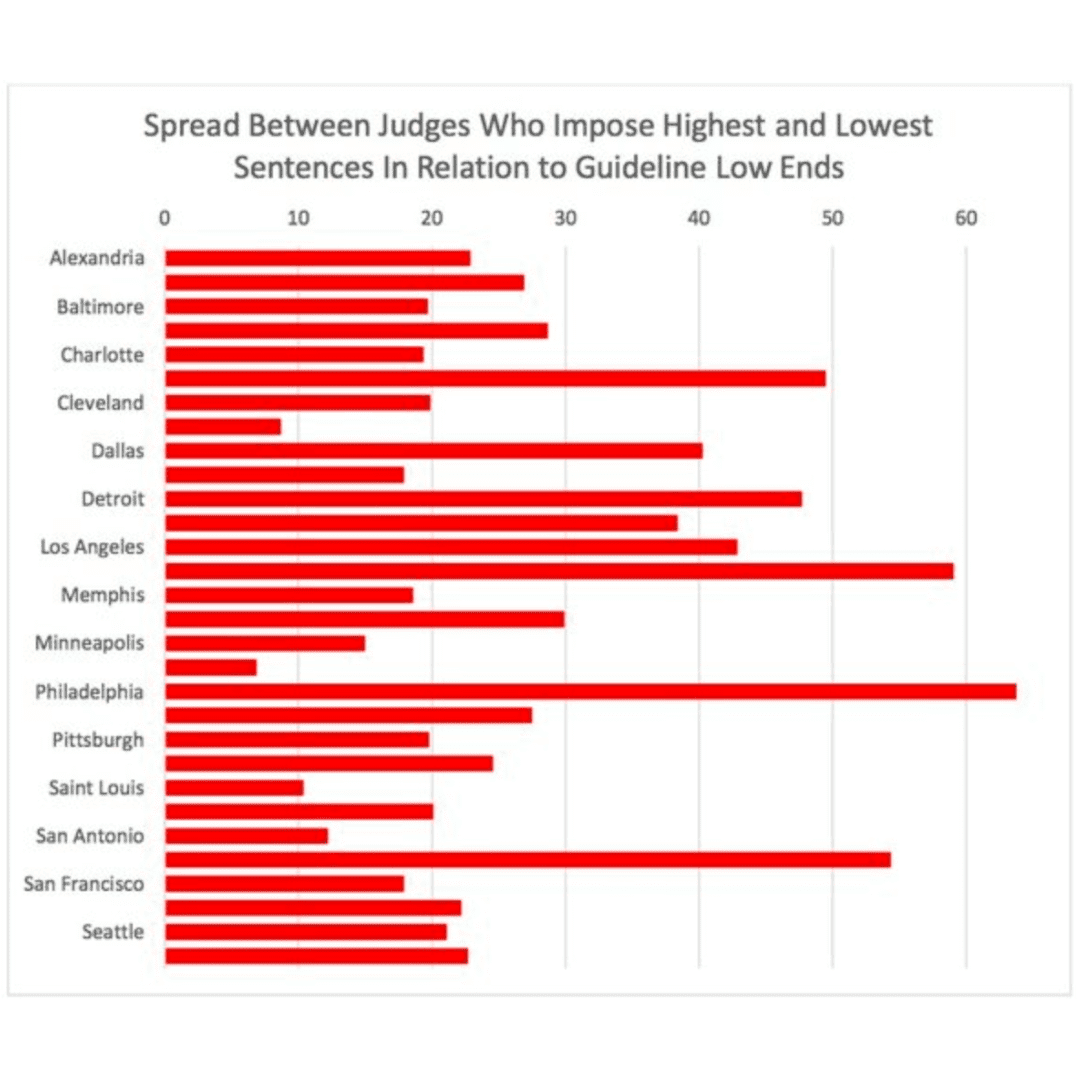

One way the government uses data in healthcare fraud cases is to compare a doctor or Medicare provider to others. Peer comparisons are an important piece of healthcare fraud investigations, and they sometimes are used as evidence in trial.

Defense counsel in a healthcare fraud case can do his or her own peer comparisons, at least using the Medicare data that is publicly available and the billing codes that are at issue. Counsel can do comparisons by going to the Medicare website, filtering the data for the billing code at issue, and then downloading the data in order to conduct some basic analysis and cleanup to make the data more user-friendly.

One big question is to see how the client compares in terms of absolute number of services or total payments based on such services. This is something that the government probably is very well aware of, and it might be the main data point that drives the government’s investigation.

Counsel should do some simple math to get what could be a more significant data point. Divide the total number of services by the total number of beneficiaries, and get the ratio of services to beneficiary. This approach was crucial in a case involving a doctor who was accused of doing unnecessary cardiac stent procedures. He was one of the top providers in the country for such stents, but he also saw more Medicare patients than most other providers. The absolute numbers looked bad and made him look like an outlier, but the ratio was in line with his peers. Basic data analysis helped put his practice into context and neutralized one piece of evidence that the government assumed would be damaging.

Ultimately, seeing how a client compares to peers can provide context that can be useful to point out to a prosecutor or to a jury. If the client is a significant outlier by one measure, see if that measure's significance is diluted by other measures or context. If the client is not an outlier, point out that this shows any improper claims were more likely to be mistakes and less likely to be the result of fraudulent practices. And if the government has not charged people who are more significant outliers than the client, try to use that to argue for a noncriminal resolution, especially if it can be shown that the government itself has handled similar cases inconsistently.

Here are two more points about peer comparisons.

When the government does a peer comparison, make sure that the government is comparing the client to a valid “peer” group. Medicare data categorizes providers by type, but those types do not reflect some significant differences. For example, some doctors may have a subspecialty that is not captured in the Medicare data, and thus would look like outliers when compared to the overall group but normal when compared to others in the subspecialty. Who are the client’s proper peers? Discuss this question with the client.

And fight back against any attempt to compare the client to a cherry-picked group of peers. This happened in one fraud case when the government tried to compare a cardiologist in a rural part of the United States that had a high incidence rate of heart disease to a few famous hospitals in other parts of the country. This was an improper peer group because it compared very different practices. Famous hospitals that draw patients from across the country and the world do not see the same kind of patients that go to a rural hospital, and those city hospitals do a different mix of services than rural hospitals. Fortunately, a judge agreed that this peer comparison was improper and excluded it from evidence.

VII. Statistical Sampling

Many white collar criminal cases involve an alleged scheme or conspiracy as well as specific transactions or incidents that are charged as specific counts of that scheme. Data analysis can help address this by focusing on the significance and meaning of those specific counts.

Those counts may or may not be fair examples of a client’s practice or the overall scheme that the government has alleged. The government may attempt to cherry-pick, but defense counsel should push back on improper extrapolations and should use data to put those cherry-picked instances into context. Pushing back is especially important in terms of loss calculations when the government tries to extrapolate based on the counts of the indictment or the evidence that was presented at trial.

One way to do this is to keep in mind how the government proves loss amounts when it wants to do it completely right. The government can use random sampling to determine loss calculations that are statistically valid and meaningful. It does not have to do such sampling in criminal cases, but this is the typical method in the healthcare context, particularly via audits and civil False Claims Act cases.

If prosecutors are not using statistical sampling, push back on this and cite the government’s own procedures back at them. Ask government witnesses about statistical sampling, and ask them to explain how it is done.

The Medicare Program Integrity Manual, chapter 4, discusses how sampling should be done in noncriminal cases involving improperly billed claims to Medicare. The government should define the set of claims that are meant to be extrapolated from, which is called the “target population” or “universe.” The government should then analyze the universe to determine the appropriate number of specific instances that should be evaluated in order to have a meaningful result, and it should randomly select those instances. The government should then have those instances evaluated and calculate a loss amount based on the review of those random selections.{10} 10 https://www.cms.gov/regulations-and-guidance/guidance/manuals/downloads/pim83c08.pdf.

If the government is basing its loss calculation on the patients it happened to interview in a healthcare fraud case, this is not valid because the government did not randomly select the patients. The government chose to interview patients based on criteria the government thought was meaningful or based on complaints by the patients. At least one judge rejected the government’s attempt to prove a “loss” amount in a restitution case in part because the patients were not randomly selected and because the number of patients interviewed was low in context. 11 United States v. Sorensen, 19 CR 745-1, oral ruling on March 20, 2024.

And if the government is basing its loss calculation on what it says is a large enough number of interviews or instances, this probably is not valid unless a statistician said it was enough.

Other ways may exist to use data analysis to push back on inflated government loss calculations. Look at the methodology that the government used and try to come up with alternative calculations that might be more reasonable.

Many healthcare fraud cases involve “upcoding,” which means a particular service was billed at a higher level of reimbursement than appropriate. The loss here should not be the total payments associated with the upcoded bills, but the difference between the upcoded bills and what should have been billed. Properly calculating loss can be especially important in cases where someone upcoded the bills without the client’s knowledge or involvement. This can significantly increase the government’s loss amount, but defense counsel can argue that this differential should not be attributed to the client.

VIII. Conclusion

Defense lawyers are practicing in an era of big data, and the government probably uses more summary charts now than it did a few decades ago. But just as the government can rely too heavily on a cooperator whom it took at face value and did not sufficiently corroborate, the government can rely too heavily on data that can backfire.

Counsel used data analysis in one trial to show that the government had presented a misleading view of a doctor’s practice, only showing a relatively small number of times when a government expert disagreed with the doctor. The government tried to counter this by highlighting one piece of data that suggested that the doctor had done an unnecessary procedure on a 92-year-old patient who died the next day.

Jurors gasped. This was the first and only time in the trial that the government had indicated that someone had suffered real physical harm as a result of one of the procedures in the case.

The government had read the data correctly, but the data was incomplete and failed to tell the whole story. The defense team quickly found and presented the full patient file, which provided the full context for the data point. The full story showed that multiple medical professionals had been involved in the patient’s care, that another doctor had recommended the procedure that the defendant had done, and that the patient’s death was due to other conditions and factors.

Defense attorneys should be skeptical of the government’s use of data, just like they would test any government witness for weaknesses and inconsistencies.

NOTE: This is an online version of an article that I originally wrote for the National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers’ Champion magazine. Please contact me if you’d like a PDF version which has more graphics and footnotes.

Truth-Default Theory and White-Collar Criminal Cases

If you practice or investigate white-collar crime, I recommend you understand Truth-Default Theory, which Malcolm Gladwell wrote about in his excellent book Talking to Strangers. As a prosecutor and as a defense lawyer, I thought a lot about the theory’s basic concepts even before I heard the term.

As Gladwell asks in his book, how did a CIA counter-intelligence agent fail to catch a double agent who was secretly working on behalf of Cuba for years? And why did people not catch onto Bernie Madoff or other Ponzi schemers until it was too late?

Because people assume that the people they’re working with or trust are telling them the truth.

Because people do not see the red flags or inconsistencies that seem obvious with the benefit of hindsight.

This is the core of the “truth-default” theory that was developed by Professor Tim Levine, whose work was the basis for much of Gladwell’s book. And this is so important that I even read some of Gladwell’s book to one client when we were preparing for trial.

Let’s go back to the CIA example. In hindsight, there were times when a CIA counter-intelligence agent almost caught the double agent (Ana Montes) as a traitor. Was he negligent for missing those signs? Gladwell writes:

“Not at all. He did what Truth-Default theory would predict any of us would do: he operated from the assumption that Ana Montes was telling the truth, and – almost without realizing it – worked to square everything she said with that assumption. We need a trigger to snap out of the default to truth, but the threshold for triggers is high.”

The problem is that when a scandal or problem arises, people want someone to blame. And once everything has blown up, the red flags seem glaringly obvious to an investigator who sees them only with the benefit of hindsight. People “must have” seen these red flags and they “must have” known what was really going on, the investigators believe.

As a result, some people get blamed and even charged with crimes because investigators and prosecutors simply cannot believe (with the benefit of hindsight) that people actually trusted the people whom they trusted. Because people default to truth as they live their lives, and investigators and prosecutors (with the benefit of hindsight) default to fraud in their investigations. The threshold for triggers that Gladwell discusses is high in real-time, but investigators sometimes apply a lower threshold because they are influenced by what they know ultimately happened.

In health care fraud, my main practice area, millions if not billions get spent every year on claims that should not have been billed. But why those improper claims were submitted is the key to how cases should get resolved, especially when multiple people are involved with the improper claims. Here were some of the questions I considered when deciding whether to bring charges in cases where it was obvious, with the benefit of hindsight, that claims had been submitted improperly:

What did each person know and do at the time of the improper claims?

Did anyone know enough that his or her involvement was a crime?

Or were people defaulting to truth and simply making mistakes or poor judgments that were unfortunate but not crimes?

Actions speak louder than words, and I tried basing my charging decisions on conduct, not just assumptions about what people knew. For example, if a doctor or company created false patient files to match the billing, this was a very strong signal that the doctor or company had not just made a mistake. Even so, the only defense that I worried about in most of my healthcare fraud cases was if the defendant were to just get up there and say that they were really sorry and now realized that they had made a mistake.

I’ve now been in private practice for more than five years, and I’ve unfortunately seen many cases where the government has incorrectly assumed that people knew more than they actually did about what was going on. I’ve even seen some instances where the government ignored evidence about how people were lied to and manipulated by others, believing that those people still “must have” known that what they were doing was wrong.

This came up a lot in a trial that I recently did involving a client who operated a durable-medical equipment company and who relied heavily on a marketer, a biller, and others. Some of those people lied to him, but he defaulted to truth and did not see the red flags that were shown to a jury years later.

Showing that the government had “defaulted to fraud” when he had actually “defaulted to truth” took a lot of work.

First, during the government’s case-in-chief, we tried to normalize the idea that everyone relies on the word of other people and that sometimes that reliance is misplaced. We did this in part by showing instances where government witnesses had relied on others within the government who turned out to have made mistakes. Everyone defaults to truth.

Second, we highlighted the huge difference between (1) what was actually true and (2) what my client believed at the time to be true. We showed that the information that the jury saw at trial was very different from the information that my client saw at the time. And we showed that some things which were red flags to the government were in fact the opposite to my client given the additional information he had and that the government had not known or dismissed.

Third, my client testified. We knew that we were asking the jury to see things the way that my client saw things at the time, and we knew that this would be difficult if he himself did not explain what he had seen.

Ultimately, the jury understood what my client thought at the time as he lived through the events, not just making faulty assumptions with the benefit of hindsight about what he “must have” thought years earlier.

If you’re a prosecutor considering charging someone, make sure that you really have more than your belief that the person “must have” known. Everyone makes mistakes and everyone defaults to truth – even you and your agents. Make sure that you can identify clear triggers or “red flag moments” that your target actually recognized at the time as such, and make sure that you can show that your target actually chose to do the wrong thing at that moment.

And if you’re a defense attorney, do what you can to have the jury understand what your client really knew, not what your client “must have” known. And look for the moment when your client actually had enough information, if he or she ever did.

In my client’s case, my client and his business partner finally consulted a lawyer who provided a detailed, written explanation of legal concerns. They did not fully understand everything the lawyer said, but they finally had enough information to reach the trigger threshold that Malcolm Gladwell talked about.

The key to the case, I believed, was what they did in that moment – they shut the business down.

Fortunately, when the jury heard the whole story, they found my client and his business partner not guilty. They had made mistakes and been too trusting, but mistakes and misplaced trust are not crimes.

Don’t just assume that people “must have known.” Look for the trigger threshold, and look at what they did at that moment.

About the Author: Stephen Lee was a federal prosecutor for 11 years and has been a defense lawyer in private practice since 2019. He was a reporter for the Chicago Tribune before becoming a lawyer.

Operation Brace Yourself: A Look at the Data

Operation Brace Yourself, the Department of Justice’s 2019 effort to combat massive fraud in terms of durable medical equipment, has gotten a lot of attention and generated many press releases, but I thought it would be useful to look closer at the underlying Medicare data, something that I’ve done extensively in prosecuting and defending health care fraud cases. This will help show the problem that the government tried to address and some issues that attorneys and healthcare professionals should consider.

Operation Brace Yourself, the Department of Justice’s 2019 effort to combat massive fraud in durable medical equipment, has gotten much attention and generated many press releases. Still, I thought it would be helpful to look at the underlying Medicare data, which I’ve extensively done in prosecuting and defending health care fraud cases. This will help show the problem that the government tried to address and some issues that attorneys and healthcare professionals should consider.

First, Operation Brace Yourself was a response to a problem that grew to staggering amounts over several years.

According to my review of Medicare data, no doctors or medical professionals anywhere in the country ordered huge amounts of prosthetics or orthotics (at least $1 million) until 2015. That year, for the first time, two providers each ordered more than $1 million of POS—I’ll call them “high-volume POS referrers.”

This was unusual. One of these high-volume POS referrers treated less than 200 Medicare beneficiaries that year while ordering POS for more than 1,500. In other words, he was ordering POS for hundreds of patients whom he probably had never even seen or treated.

And the number of such high-volume POS referrers went up year after year. By 2018, about 170 Medicare providers ordered more than $1 million of POS that year, with about 24 ordering more than $5 million each (including one doctor who ordered more than $15 million), according to billing data.

This was a huge change in billing patterns—a very concentrated amount of POS orders from physicians who often had not ordered much in POS beforehand. Some of these physicians were in specialties that ordinarily would not be associated with ordering large amounts of expensive back braces and knee braces.

There were many family practitioners, many nurse practitioners, some OB-GYNs, an ENT (ear, nose, and throat doctor), and even a psychologist and a psychiatrist. Many of these doctors and practitioners ordered braces for thousands of patients (based on data submitted by DME suppliers) while actually treating a much smaller number of patients (based on the Part B data submitted by the doctors and practitioners themselves).

These are massive red flags in the data, and the Operation Brace Yourself cases explain what was going on. As we now know from the publicly filed documents, many of these doctors participated in schemes involving “telemedicine.” However, “telemedicine” here was unlike the virtual visits many of us used because of the pandemic.

In everyday situations involving DME, the doctor treats the patients and orders DME as part of the patients’ overall care. But here, the doctor was not the primary decision-maker, often had no prior relationship with the patients, and often had little if any interaction with the patients - sometimes just a telephone call. In the cases that the government calls “telemedicine” cases, businesspeople and marketers are the main drivers of the process, and doctors often sign off on expensive orders based on minimal patient information and often without fully understanding what is going on.

The diagram below shows how a prosthetics order should work in normal circumstances. A patient goes to a doctor, the doctor places an order to a supplier, and the supplier bills Medicare for the DME that the patient receives and uses.

The following diagram shows how prosthetics orders in the Brace Yourself cases came about. According to the claims submitted to Medicare, everything worked as usual.

But in reality, patients were recruited by call centers, a doctor who had little to no interaction with a patient signed orders for braces, and a broker sold the patient information and those signed orders to suppliers who then billed Medicare for expensive items that patients often did not need or even use.

Overall, this is a complex system set up to defraud Medicare by billing for unnecessary items in ways that appear legitimate.

Many of these cases involve some telephone contact with a doctor. Still, it’s more beneficial to consider these cases as “doctor-enabled” healthcare fraud, in contrast to classic healthcare fraud schemes where the doctor drives the fraud. Based on my experience, what the government calls “telemedicine” fraud is just a slight evolution of similar schemes in other areas such as home health, hospice, and genetic testing – all cases where the doctor enables the fraud rather than driving the fraud. “Telemedicine” focuses on one delivery system rather than the more significant problem.

Whatever you call it, all of this had enormous consequences on Medicare.

In 2018 alone, Medicare spent almost $500 million on POS ordered by these high-volume POS referrers. From 2015 to 2019, Medicare paid over $1.1 billion on POS allegedly ordered by these people.

Second, Operation Brace Yourself does appear to have had a significant impact on the problem.

The government charged and arrested multiple people in April 2019, and the charges appear to explain a significant drop-off in activity over the entire year. The number of providers responsible for more than $1 million of POS dropped, and Medicare spending on POS for those high-volume referrers dropped by about 30 percent. I’ve heard one government official say there was a $2 billion decrease in spending in the 18 months after Operation Brace Yourself, a sign of how big the problem had gotten and how much it would have cost Medicare had the problem continued.

Third, the government has charged and convicted several doctors who ordered large amounts of POS.

According to Medicare data, as of June 2022, several doctors who have been charged and convicted are listed below, along with the amounts of POS they ordered.

Dr. Kenneth Pelehac was charged in 2022, pled, and agreed to cooperate, but has not yet been sentenced—total Medicare POS payments of more than $17 million.

Dr. Ravi Murali - charged in 2020, pled and sentenced to 54 months imprisonment—total Medicare POS payments of more than $13 million.

Dr. Randy Swackhammer - began cooperating with the government in early 2019 (while Operation Brace Yourself was still a covert operation) and made recordings of others. Charged in 2019, pled, cooperated, and sentenced to probation—total Medicare POS payments of over $7 million.

At least two high-volume referrers who were charged are set for trial in late 2022.

At the same time, as of June 2022, most high-volume referrers, including some doctors with very high POS payments associated with them, have not been charged.

For example, according to data, the doctor who ordered the most POS ($24 million in total, including a staggering $17 million in just 2019 alone) has not been charged with a crime as of June 2022. According to data, she treated about 400 patients in 2019 while ordering POS for thousands of patients she never treated – more than 8,000. I assume the government has looked at this doctor, who probably got involved with “telemedicine” because she was in bad shape financially - she filed for bankruptcy in early 2019 and mentioned her work in “telemedicine” in her bankruptcy petition. Whether she gets charged will probably depend on whether the government can prove that she knew that her conduct was illegal.

Fourth, these doctors appear to have made relatively little from their involvement compared to the DME suppliers.

According to publicly filed documents, several doctors who have been charged made $20 to $40 per order they signed. In one example, the doctor made $30 for authorizing a knee brace for a patient he had never met or spoken to, while the DME company was paid more than $300 for that brace. Plea agreements with two doctors show that the doctors made less than $200,000 each for their parts in the overall crime, while Medicare paid millions of dollars to the DME suppliers who used the doctors’ orders.

In contrast to some of these doctors, some patient brokers and DME suppliers who have been charged and convicted as part of Operation Brace Yourself reportedly made far more money. In one case, two people were sentenced to more than 12 years in prison for a scheme that allegedly resulted in more than $27 million of Medicare payments, including millions that the defendants transferred overseas. Another man was sentenced to 15 years in prison for selling patient information; he notably engaged in this conduct before Operation Brace Yourself and continued the conduct even afterward.

So what can attorneys and health care providers take from all this?

First, there is a lot of data out there, both publicly and privately, and people should get a better handle on the data sooner rather than later. Many of the high-volume referrers probably had no idea how much money was being spent under their name and how easily the data pointed to them, and they probably would have withdrawn quickly. They could have avoided prosecution if they had known. Some of these doctors might have been the victims of identity theft, and a closer look at their data might have caught that, too.

If a doctor has already been charged, it may be helpful to know how the doctor compares to his or her peers. Such comparative data may help position the doctor better, at least for sentencing, especially when it is clear that many people have not been charged for what seems like similar conduct.

Second, many doctors who ordered large amounts of POS were in fields not generally associated with prosthetics or orthotics. Some of these doctors probably thought this work was a way to supplement their income without realizing the massive risks they were taking by getting involved in unfamiliar areas. Doctors should be careful when switching fields or going outside their specialties and not just rely on what their employers tell them.

Third, the government has to prove “willfulness” to prosecute someone for health care fraud or kickbacks – basically, the government has to prove that people knew that what they were doing was illegal and did it anyway. That can be difficult when the doctors have little knowledge of the overall system and receive relatively small payments. If a doctor were naïve, careless, or gullible, the doctor would not have the “willfulness” necessary to be convicted of healthcare fraud. This might explain why many high-volume referrers have not been charged with a crime.

At the same time, the government can prove willfulness more easily when fake documents are used, such as when businesspeople or DME suppliers try to make payments to doctors look like “marketing” expenses, indicating that they know that the payments violate the Anti-Kickback Statute.

Doctors involved with DME or other high-risk areas can alert themselves to potential “doctor-enabled” healthcare fraud by asking a few questions.

Do you know where your patients came from? Are your patients reaching out for help, or have marketers solicited them?

Are you treating the patient or just ordering one or more particular items or services that you would not order in your typical practice?

Is everything true before you sign if you are given forms or EMRs to fill out? If not, this could be a red flag for fraud.

How are you getting paid? Are your services being billed to a patient’s insurance, or are they effectively tied to your ordering another service or item? If the latter, your payments could be seen more like a kickback.

The Stephen Lee Law legal blog covers various topics, including healthcare fraud defense, investigations, data analytics, and the federal anti-kickback statute.

For further insights into Operation Brace Yourself or legal guidance on healthcare fraud defense, please contact Stephen Lee Law.

How to Build a Smoking Gun: Effectively Using Data and Documents

Imagine that you are an investigator and have access to an insider whose credibility could not be impeached and that this insider could lay out exactly what the defendant did with the money or told his victims. You would spend days with that insider, figuring out how to ask the right questions to elicit the information you need to make your case. Documents and data can be the equivalent of those potential insiders, and prosecutors and agents should treat them as such. With some time and the right mindset, documents and data can be turned into the equivalent of a “smoking gun,” strengthening cases and even helping make them in the first place.

Imagine you are an investigator with access to an insider whose credibility cannot be impeached. This insider can precisely detail what the defendant did with the money or told his victims. You would spend days with that insider, figuring out how to ask the right questions to elicit the necessary information to make your case.

Documents and data can be the equivalent of such insiders, and prosecutors and agents should treat them accordingly. With some time and the right mindset, documents, and data can be turned into the equivalent of a “smoking gun,” strengthening cases and even helping make them in the first place.

I was a federal prosecutor for 11 years and a reporter for the Chicago Tribune. I will talk about some examples from real-life criminal cases below, but let’s start with two examples from journalism (one fictional, one real) that show how powerful this kind of work can be.

In the popular thriller The Girl With The Dragon Tattoo, the main character (an investigative journalist) tries to discover what happened to a girl who has been missing for decades. The big break comes when the journalist discovers archived photos from a parade the missing girl attended. Each image, in and of itself, is meaningless. But then the journalist does something with the pictures. He takes all the photos and puts them chronologically focused on the missing girl.

The resulting sequence shows the girl enjoying a parade and reacting with shock and horror when she sees something on the other side of the street. Something happened at that parade that changed everything, which is a vital part of the mystery.

Each photo was just noise on its own, but when aggregated, the overall sequence changed the entire course of the investigation.

Scene from the film, Spotlight

In Spotlight, the 2015 Oscar-winning movie based on actual events, Boston Globe reporters are investigating the sexual abuse scandal within the Catholic Church. One reporter looks up a suspect priest in the archdiocese’s annual directory and realizes that the archdiocese had used a euphemism to refer to the priest’s location. The reporters then recognized that the archdiocese had been using such euphemisms to refer to other priests and that the archdiocese had thus left a coded guide of the abuse in its directories.

A montage sequence ensues of reporters going through directories, climaxing with, of all things, the completion of a spreadsheet.

Spreadsheet from the film, Spotlight

Three Pulitzer Prize-winning Boston Globe reporters who did the work in real life — Walter Robinson, Michael Rezendes, and Sacha Pfeiffer — described it as “three and a half weeks of agony” in a telephone interview. They sometimes did the work in pairs to relieve the monotony on the eyes, with one reporter reading off from a directory and another person entering the data. But it was worth it. They said the resulting database was invaluable. The work showed that the individual examples they had heard about were not isolated and showed a larger pattern at work.

These fictional and real journalists made these breakthroughs by investing time and resources into aggregating little bits of information into something that no single witness would have given them, making them the equivalent of smoking guns. Prosecutors and agents can achieve similar results by thinking beyond the witnesses they will interview and investing time and resources into aggregating evidence into powerful tools.

I take three general approaches to data and documents in my investigations.

I. Count Something

Whether you are dealing with bank records, emails, or boxes of documents, simply counting and categorizing critical pieces of information can answer essential questions and yield robust evidence. In his book Better: A Surgeon’s Notes on Performance, Dr. Atul Gawande suggested that one way of becoming a better doctor was to count something: “If you count something you find interesting, you will learn something interesting.” This advice can also be useful in criminal investigations and trials.

Who are people talking to, how often, and what about?

These are things that can be quantified in potentially powerful ways.

Take the 2014 trial of former Connecticut Governor John Rowland. In describing the evidence that led to the jury’s guilty verdicts, a New York Times reporter described the government’s summary witness as providing “several powerful punches” simply by categorizing emails and phone records and counting them.

One issue at trial had been Rowland’s contract with a nursing home owned by a cooperating codefendant — was it a legitimate contract for services, or was it a way to disguise campaign work? To help address this, the summary witness, a retired postal inspector, counted their emails and found that the vast majority was related to campaign business and that only a small number was related to the nursing home’s business.

Re-creation of data from United States v. Rowland

Where is the money coming from, and where is the money going?

In Ponzi scheme cases, analysis of the bank records typically will reveal some common traits: (1) money coming in primarily from new investors, (2) little money going out for the kinds of investments that the fraudster had promised, and (3) some disconnect showing how the enterprise’s obligations far outstrip the enterprise’s actual assets or funds.

That is what happened with Charles Ponzi himself. Ponzi told investors in early 1920 that he could use their money to make huge profits using “international reply coupons” that could be bought at low rates in some countries and worth more in others. He promised fifty percent returns in just months.

The graph below summarizes the amount of money that Ponzi could collect from people in 1920 as his scheme suddenly grew. The scheme started small but proliferated before suddenly collapsing in the summer of 1920.

Chart based on reporting done by Mitchell Zuckoff in Ponzi’s Scheme: The True Story of a Financial Legend (2005).

Had Ponzi been just a lousy businessman rather than a fraudster, there should have been expenses showing that he was implementing the business model he had been pitching. There were not. The money that Ponzi collected went to hire more people to solicit more investors, to pay down debts, and to enjoy and show the wealth that made him look successful — suits for himself and jewels for his wife, a custom-made limousine, and a seven-bedroom house. Ponzi claimed to have given some money to a man who went to Italy to buy the international reply coupons necessary for his model to work. Still, there appears to be no evidence that this man existed.

Counting up the money can be a big part of going after people like Ponzi. Most money will go to maintaining or expanding the scheme (the employees that Ponzi hired and branches he opened to solicit more investors) and for the fraudster’s benefit, and little, if any, will be used to do what the fraudster has claimed to be doing.

Individual acts vs. a fraud scheme?

Anyone can make a mistake, which is generally not a crime. But if you can repeatedly show that someone was making the same mistake, it becomes much easier to show that a crime was committed.

The James Bond villain Goldfinger put it well: One time is luck, and twice is a coincidence, but the third time is enemy action. Similarly, one time may be an accident or mistake, two or three times may be negligence or sloppiness, but time after time is a scheme.

For example, in a campaign finance case (United States v. Whittemore), the defendant funneled money through multiple intermediaries to the ultimate recipient. The government used charts to show that each intermediary’s contribution followed the same pattern. One day alone, the defendant transferred $145,000 to seventeen relatives and employees, which were characterized as “bonuses” or “gifts,” and simultaneously encouraged them to make contributions, sometimes explicitly saying that the money was intended to cover the cost of the contribution. At trial, the government introduced charts showing each step being repeated repeatedly, a powerful depiction of the defendant’s conduct and intent.

From United States v. Whittemore

One “bonus” or “gift” might have been just that, but all these bonuses and gifts, aggregated together, were strong evidence of a scheme and of criminal intent.

Similarly, healthcare fraud cases can benefit significantly from simply counting something odd. People committing healthcare fraud typically have gotten very good at papering their files to fool an auditor, looking only at a few randomly selected claims in isolation. But if you step back and look at the files overall, that may reveal some ridiculous pattern that will be robust evidence of the overall fraud.