Federal Sentencing Disparities Uncovered: A Closer Look at Federal Guidelines

A recent report by the U.S. Sentencing Commission sheds new light on the prevalence of unwarranted sentencing disparities in federal cases. It should attract more attention from prosecutors, defense attorneys, judges, and the public.

Introduction to Sentencing Discrepancies

The sentencing guidelines were created partly to deal with a specific problem: the concern that similarly situated defendants who committed similar crimes were getting different sentences based on which judge the defendant was assigned to. Under the guidelines, a judge must start sentencing by calculating the offense level reflecting the defendant's offense, the defendant's criminal history, and a guideline range reflecting the sentence the judge must consider in sentencing the defendant. The U.S. Supreme Court held in the 2005 U.S. v. Booker decision that the sentencing guidelines were not mandatory but still recognized the importance of promoting uniformity in sentencing.

Unfortunately, new data from the commission shows that post-Booker federal sentencing is not going as Congress and the Supreme Court had hoped.

The Role of the Sentencing Guidelines Post-Booker

This most recent set of such data is contained in "Intra-City Differences in Federal Sentencing Practices," a report issued in January 2019. In the report, the commission looked at almost 150,000 cases in which judges in 30 cities had significant discretion in sentencing and where there was sufficient information to make comparisons. Overall, the cases were about 30 percent drug cases, 14 percent illegal entry or re-entry cases, 13 percent fraud cases, 13 percent gun cases, and 29 percent other cases.

The report has a wealth of information and is worth studying by lawyers in the 30 cities covered. I've designed the charts below to highlight the overall trends and to make comparisons between those cities more straightforward.

Analyzing the Data: Disparities Within Cities

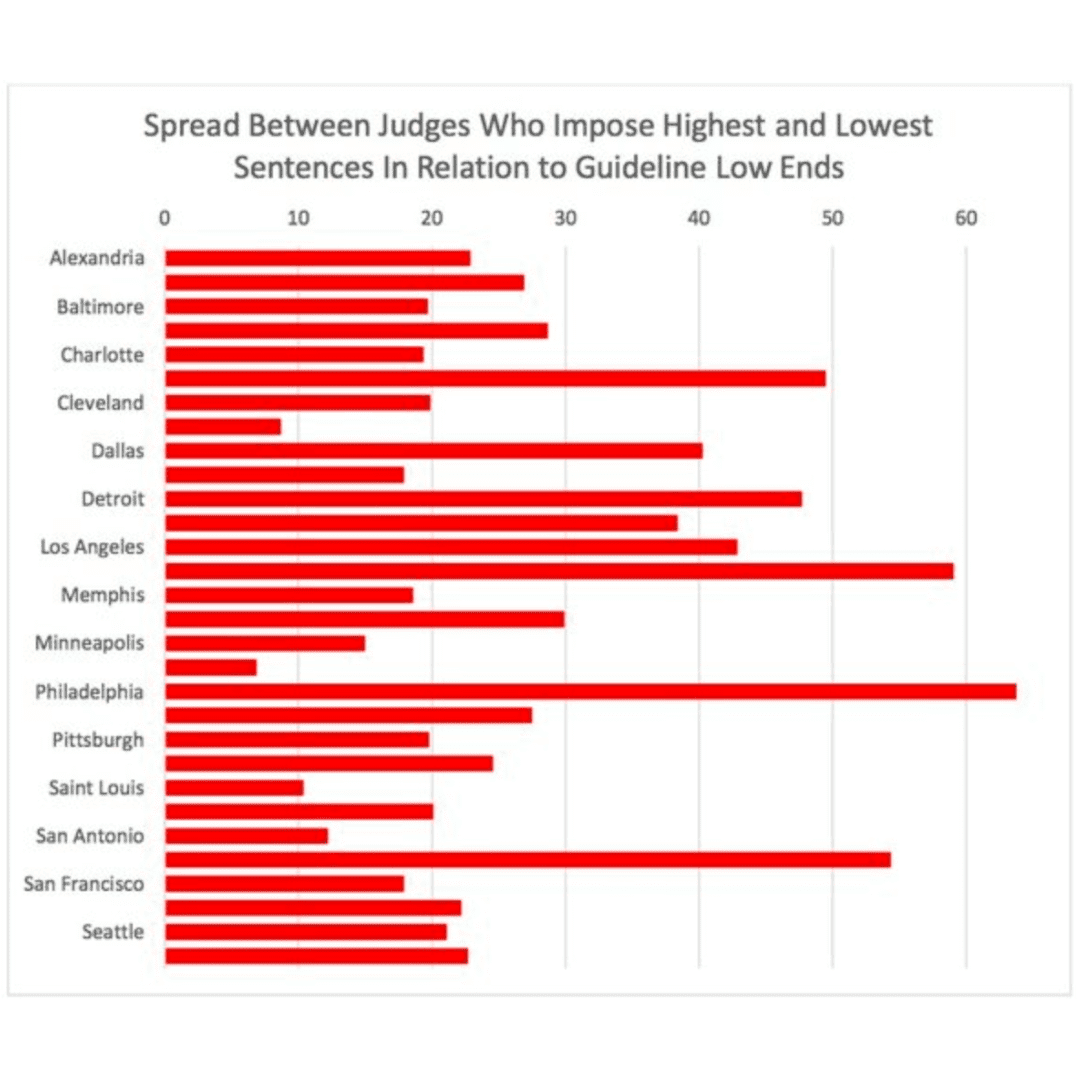

First, the Sentencing Commission found vast differences in sentences imposed by judges within the same city, concluding: "In most cities, the length of a defendant's sentence increasingly depends on which judge in the courthouse is assigned to his or her case."

Philadelphia provides the most extreme example of the 30 cities studied by the commission. In Philadelphia, one judge, on average, gave sentences more than 20 percent greater than the city average, while another judge, on average, gave sentences around 40 percent lower than the city average. Philadelphia thus had the most significant "spread" of any major city, at 63.8. Manhattan had the second-highest spread (59.1), with two judges on average giving sentences more than 20 percent above the city average and one judge on average giving sentences more than 30 percent below the city average.

The Extent of Below-Guideline Sentences

Second, the Sentencing Commission found that most judges nationwide give, on average, sentences well below the low end of the applicable guideline range. Out of the 30 cities studied, the average judge gave sentences below the low end of the guidelines in all but one. Average sentences in eight cities (Alexandria, Boston, Chicago, Los Angeles, Manhattan, Portland, Salt Lake City, and Seattle) were more than 25 percent below the low end of the average guideline range.

Judicial Discretion and the Guidelines

Third, there appears to be a divide between judges regarding the weight of the guidelines. Of the 339 judges whom the commission studied, there were no judges who were, on average, giving sentences significantly more significant than the guideline minimum, but more than 90 percent of judges gave average sentences below the guideline minimum. No judge gave sentences at or above the guideline minimum in Manhattan, even those who gave sentences far more significant than their peers. Chicago only had one judge out of 24 whose average sentence was at or above the guideline minimum.

Lawyers practicing in the federal courts probably already knew much of this anecdotally, but the commission's data analysis puts some hard numbers on trends that lawyers and policymakers should be aware of and address.

The commission's report does not address why these differences in sentencing and these variations from the guidelines are occurring. The commission does look at the mix of cases that different judges and districts had, and this may explain some of the patterns, but probably not much, given that the analysis period covered several years' worth of sentencings.

However, looking at some of the publicly available, case-specific data may provide clues as to what is going on. Many lawyers may not be aware of this. Still, the commission has made a lot of anonymized data about sentencings available: first, in SAS and SPSS files that can be accessed via the commission's website, and second, in additional formats that can be accessed via the University of Michigan's Institute for Social Research.

My analysis of the fiscal year 2016 data online via the Institute for Social Research points to some possible factors.

First, sentences appear to go further down from the guidelines as the sentencing ranges increase. The graph below shows that economic crimes (as indicated by Guideline 2B1.1) and drug crimes (as indicated by Guideline 2D1.1) result in sentences further below the guidelines as the ranges exceed 60 months (five years). Large cities such as New York and Chicago tend to see cases with more significant loss amounts and drug quantities. They thus may see more sentences below-guideline than in smaller cities with lower loss amounts and drug quantities.

Second, as seen in the graph below, many economic crime offenders are getting sentences below guidelines, especially as loss amounts go up. This may reflect a discount of large loss amounts, perhaps a discounting of some of the sentencing enhancements in 2B1.1, or perhaps credit for reputational harm and loss of professional licenses.

More research and discussion are needed, but there is enough data now to make the discussion about more than just anecdotes and outlier cases. The commission's data analysis raises serious questions that should impact sentencing recommendations and perhaps help reopen a debate about balancing judicial discretion with the goal of uniformity.

Navigating New Norms: Federal Prosecutors and Sentencing Guidelines

In the wake of the U.S. Sentencing Commission's revealing data on federal sentencing practices, a paradigm shift appears necessary for federal prosecutors. Traditionally guided by the Justice Manual to recommend sentences within the guideline ranges, prosecutors now face a landscape where judges frequently impose sentences below these ranges, especially in high-guideline cases.

This trend challenges the conventional prosecutorial strategy and calls for a reevaluation of sentencing recommendations to align with the evolving judicial discretion and the overarching goal of mitigating unwarranted sentencing disparities. As the legal community grapples with these findings, the implications for federal prosecutors, defense attorneys, and judges underscore a critical moment of reflection and potential recalibration in federal sentencing practices.

Implications for Federal Prosecutors

First, federal prosecutors should reconsider their approach to sentencing recommendations. The U.S. Department of Justice's Justice Manual strongly suggests that prosecutors recommend sentences within the guidelines range but also imposes a duty on the prosecutor to recommend a sentence that would not result in an unwarranted sentencing disparity.

Judges impose below-guideline sentences, particularly in cases with high guideline ranges, so prosecutors should consider recommending more that reflect consistency with the imposed sentences. Prosecutors should not make high opening bids with the expectation that the judge will split the difference. Prosecutors should make recommendations to meet all the Section 3553 factors, including avoiding unwarranted sentencing disparities. The reality is that within-guideline sentences sometimes might be unnecessary given the sentences imposed post-Booker.

Prosecutors may also want to reconsider some recommendations tied to the guidelines' low end. If the average sentence in a district is 20 percent or more below the guidelines, then recommending 20 percent off the low end of the guidelines for a cooperator does not mean much.

Strategic Considerations for Defense Attorneys

Second, defense attorneys should consider using the data in the right circumstances. They can look at the anonymized data available online and see how similar defendants have been sentenced and point out cases or trends favorable to their clients. Defense attorneys in those few courtrooms where the average sentence is at or above the guideline minimum may want to point out that a sentence within the guidelines might create an unwarranted sentencing disparity, given what other judges are doing.

The Role of Judges in Addressing Disparities

Third, judges may want to discuss with their peers how their sentencing approaches align with the guidelines and Congress' intent to avoid unwarranted sentencing disparities, particularly in districts with wide ranges in sentences.

Policy Considerations and Future Directions

Fourth, policymakers and the public may want to examine the sentencing guidelines given this data. Are specific guidelines resulting in offense levels that are too high? Or does the sentencing table need to be recalibrated, as a one-level increase in a defendant's offense level means two or three more months at the lower levels but 30 or more months at the higher levels? And those courtrooms where sentences are meager might warrant some further examination.

Conclusion: Balancing Discretion and Uniformity

The Booker decision properly gave judges discretion in individual cases. Still, the effects on overall fairness need to be studied more, as many defendants' sentences appear to depend significantly on the judge that they end up standing before.

The Stephen Lee Law legal blog covers various topics, including healthcare fraud defense, investigations, data analytics, and the federal anti-kickback statute.

For further insights into federal sentencing disparities or legal guidance with healthcare fraud defense, please contact Stephen Lee Law.