Legal Blog

How to Build a Smoking Gun: Effectively Using Data and Documents

Imagine that you are an investigator and have access to an insider whose credibility could not be impeached and that this insider could lay out exactly what the defendant did with the money or told his victims. You would spend days with that insider, figuring out how to ask the right questions to elicit the information you need to make your case. Documents and data can be the equivalent of those potential insiders, and prosecutors and agents should treat them as such. With some time and the right mindset, documents and data can be turned into the equivalent of a “smoking gun,” strengthening cases and even helping make them in the first place.

Imagine you are an investigator with access to an insider whose credibility cannot be impeached. This insider can precisely detail what the defendant did with the money or told his victims. You would spend days with that insider, figuring out how to ask the right questions to elicit the necessary information to make your case.

Documents and data can be the equivalent of such insiders, and prosecutors and agents should treat them accordingly. With some time and the right mindset, documents, and data can be turned into the equivalent of a “smoking gun,” strengthening cases and even helping make them in the first place.

I was a federal prosecutor for 11 years and a reporter for the Chicago Tribune. I will talk about some examples from real-life criminal cases below, but let’s start with two examples from journalism (one fictional, one real) that show how powerful this kind of work can be.

In the popular thriller The Girl With The Dragon Tattoo, the main character (an investigative journalist) tries to discover what happened to a girl who has been missing for decades. The big break comes when the journalist discovers archived photos from a parade the missing girl attended. Each image, in and of itself, is meaningless. But then the journalist does something with the pictures. He takes all the photos and puts them chronologically focused on the missing girl.

The resulting sequence shows the girl enjoying a parade and reacting with shock and horror when she sees something on the other side of the street. Something happened at that parade that changed everything, which is a vital part of the mystery.

Each photo was just noise on its own, but when aggregated, the overall sequence changed the entire course of the investigation.

Scene from the film, Spotlight

In Spotlight, the 2015 Oscar-winning movie based on actual events, Boston Globe reporters are investigating the sexual abuse scandal within the Catholic Church. One reporter looks up a suspect priest in the archdiocese’s annual directory and realizes that the archdiocese had used a euphemism to refer to the priest’s location. The reporters then recognized that the archdiocese had been using such euphemisms to refer to other priests and that the archdiocese had thus left a coded guide of the abuse in its directories.

A montage sequence ensues of reporters going through directories, climaxing with, of all things, the completion of a spreadsheet.

Spreadsheet from the film, Spotlight

Three Pulitzer Prize-winning Boston Globe reporters who did the work in real life — Walter Robinson, Michael Rezendes, and Sacha Pfeiffer — described it as “three and a half weeks of agony” in a telephone interview. They sometimes did the work in pairs to relieve the monotony on the eyes, with one reporter reading off from a directory and another person entering the data. But it was worth it. They said the resulting database was invaluable. The work showed that the individual examples they had heard about were not isolated and showed a larger pattern at work.

These fictional and real journalists made these breakthroughs by investing time and resources into aggregating little bits of information into something that no single witness would have given them, making them the equivalent of smoking guns. Prosecutors and agents can achieve similar results by thinking beyond the witnesses they will interview and investing time and resources into aggregating evidence into powerful tools.

I take three general approaches to data and documents in my investigations.

I. Count Something

Whether you are dealing with bank records, emails, or boxes of documents, simply counting and categorizing critical pieces of information can answer essential questions and yield robust evidence. In his book Better: A Surgeon’s Notes on Performance, Dr. Atul Gawande suggested that one way of becoming a better doctor was to count something: “If you count something you find interesting, you will learn something interesting.” This advice can also be useful in criminal investigations and trials.

Who are people talking to, how often, and what about?

These are things that can be quantified in potentially powerful ways.

Take the 2014 trial of former Connecticut Governor John Rowland. In describing the evidence that led to the jury’s guilty verdicts, a New York Times reporter described the government’s summary witness as providing “several powerful punches” simply by categorizing emails and phone records and counting them.

One issue at trial had been Rowland’s contract with a nursing home owned by a cooperating codefendant — was it a legitimate contract for services, or was it a way to disguise campaign work? To help address this, the summary witness, a retired postal inspector, counted their emails and found that the vast majority was related to campaign business and that only a small number was related to the nursing home’s business.

Re-creation of data from United States v. Rowland

Where is the money coming from, and where is the money going?

In Ponzi scheme cases, analysis of the bank records typically will reveal some common traits: (1) money coming in primarily from new investors, (2) little money going out for the kinds of investments that the fraudster had promised, and (3) some disconnect showing how the enterprise’s obligations far outstrip the enterprise’s actual assets or funds.

That is what happened with Charles Ponzi himself. Ponzi told investors in early 1920 that he could use their money to make huge profits using “international reply coupons” that could be bought at low rates in some countries and worth more in others. He promised fifty percent returns in just months.

The graph below summarizes the amount of money that Ponzi could collect from people in 1920 as his scheme suddenly grew. The scheme started small but proliferated before suddenly collapsing in the summer of 1920.

Chart based on reporting done by Mitchell Zuckoff in Ponzi’s Scheme: The True Story of a Financial Legend (2005).

Had Ponzi been just a lousy businessman rather than a fraudster, there should have been expenses showing that he was implementing the business model he had been pitching. There were not. The money that Ponzi collected went to hire more people to solicit more investors, to pay down debts, and to enjoy and show the wealth that made him look successful — suits for himself and jewels for his wife, a custom-made limousine, and a seven-bedroom house. Ponzi claimed to have given some money to a man who went to Italy to buy the international reply coupons necessary for his model to work. Still, there appears to be no evidence that this man existed.

Counting up the money can be a big part of going after people like Ponzi. Most money will go to maintaining or expanding the scheme (the employees that Ponzi hired and branches he opened to solicit more investors) and for the fraudster’s benefit, and little, if any, will be used to do what the fraudster has claimed to be doing.

Individual acts vs. a fraud scheme?

Anyone can make a mistake, which is generally not a crime. But if you can repeatedly show that someone was making the same mistake, it becomes much easier to show that a crime was committed.

The James Bond villain Goldfinger put it well: One time is luck, and twice is a coincidence, but the third time is enemy action. Similarly, one time may be an accident or mistake, two or three times may be negligence or sloppiness, but time after time is a scheme.

For example, in a campaign finance case (United States v. Whittemore), the defendant funneled money through multiple intermediaries to the ultimate recipient. The government used charts to show that each intermediary’s contribution followed the same pattern. One day alone, the defendant transferred $145,000 to seventeen relatives and employees, which were characterized as “bonuses” or “gifts,” and simultaneously encouraged them to make contributions, sometimes explicitly saying that the money was intended to cover the cost of the contribution. At trial, the government introduced charts showing each step being repeated repeatedly, a powerful depiction of the defendant’s conduct and intent.

From United States v. Whittemore

One “bonus” or “gift” might have been just that, but all these bonuses and gifts, aggregated together, were strong evidence of a scheme and of criminal intent.

Similarly, healthcare fraud cases can benefit significantly from simply counting something odd. People committing healthcare fraud typically have gotten very good at papering their files to fool an auditor, looking only at a few randomly selected claims in isolation. But if you step back and look at the files overall, that may reveal some ridiculous pattern that will be robust evidence of the overall fraud.

One common type of healthcare fraud involves doctors billing routine patient visits as if the visits were more complicated than they were. Complicated visits should take more time, and the American Medical Association includes typical times for each billing level. Adding up the number of visits in a day and multiplying them by the associated time can yield robust evidence of fraud, especially when the totals become particularly ridiculous, such as the doctors who regularly bill more than twenty-four hours’ worth of visits in a single day. Theoretically possible, but extremely unlikely.

Look for something weird, untrue, or inconsistent in the files and data, and you can turn it into something powerful at trial.

II. Contrast Something

Fraud cases often involve defendants making their victims (investors, clients, Medicare) believe that defendants are doing one thing when the reality is otherwise. They create a fake world that appears legitimate from the inside. Documentary evidence and summary charts can help jurors escape the phony world and see the reality themselves.

In Ponzi scheme cases, there will probably be a stark contrast between what the defendant says and what he is doing. Charles Ponzi told people that he was arbitraging postal reply coupons. Still, there were not enough coupons in circulation to make all the money that Ponzi was promising, and Ponzi was not buying large quantities of coupons as he would have had to if he meant what he was saying. The chart below shows this comparison.

Similarly, when forensic accountant Bruce Dubinsky tried to show that Bernie Madoff was running a Ponzi scheme, there was a contrast between the stock purchases shown in Madoff’s customer ledgers and those that occurred. Dubinsky found that ledgers reported purchases on particular days that were in greater volume than had happened in the entire stock market, and he discovered that ledgers reported purchases at prices that were lower than all the reported prices in the whole stock market.

From Dubinsky’s trial slides

From Dubinsky’s trial slides

Dubinsky’s slides were admitted at the trial of some of Madoff’s associates via his role as an expert. Still, many of them could have been admitted under Rule 1006, which allows a summary of voluminous records. Dubinsky testified at trial that he spent days going through thousands of banker boxes of Madoff documents housed in a warehouse on Long Island, and his work summarized the review of those and other voluminous records.

Contrasting lies with reality can work in prosecuting other types of fraud. In the late 1990s and early 2000s, a defendant conspired with a courthouse procurement officer to rig bids and overcharged the court (United States v. Millkiewicz). The government used multiple summary charts to prove the fraud, including one that juxtaposed (1) what the defendant purchased from his vendors, based on a summary of roughly 1,300 pages of records, and (2) what the defendant billed to the district court. Here is a visualization of one such comparison from October 2001:

Re-creation of data from United States v. Millkiewicz

Rather than making the jury compare vast amounts of records, charts like this can work for the jury. With the chart, the jury can more easily see that the court had paid for 100 more cartons of paper than the defendant himself could have delivered in October 2001.

In healthcare fraud cases, the records and data of legitimate providers can also strongly contrast with a defendant’s fraud. For example, nursing agencies and doctors often claim that patients are “confined to the home” for extended periods in home health cases. The agencies and doctors can submit claims, making the patients appear sick. Still, the files and data created by patients’ other providers can show that the patients were leaving their homes during the same periods and were in stable condition.

In a case involving cosmetic light treatments that were falsely billed as destroying precancerous lesions (United States v. Memar), the government learned that one patient had gotten such treatments while seeing another dermatologist. The government contrasted the two doctors’ records in a timeline that showed that (a) the defendant was allegedly destroying lesions nine times over a single year and (b) another doctor saw no such lesions during that same year.

From United States v. Memar

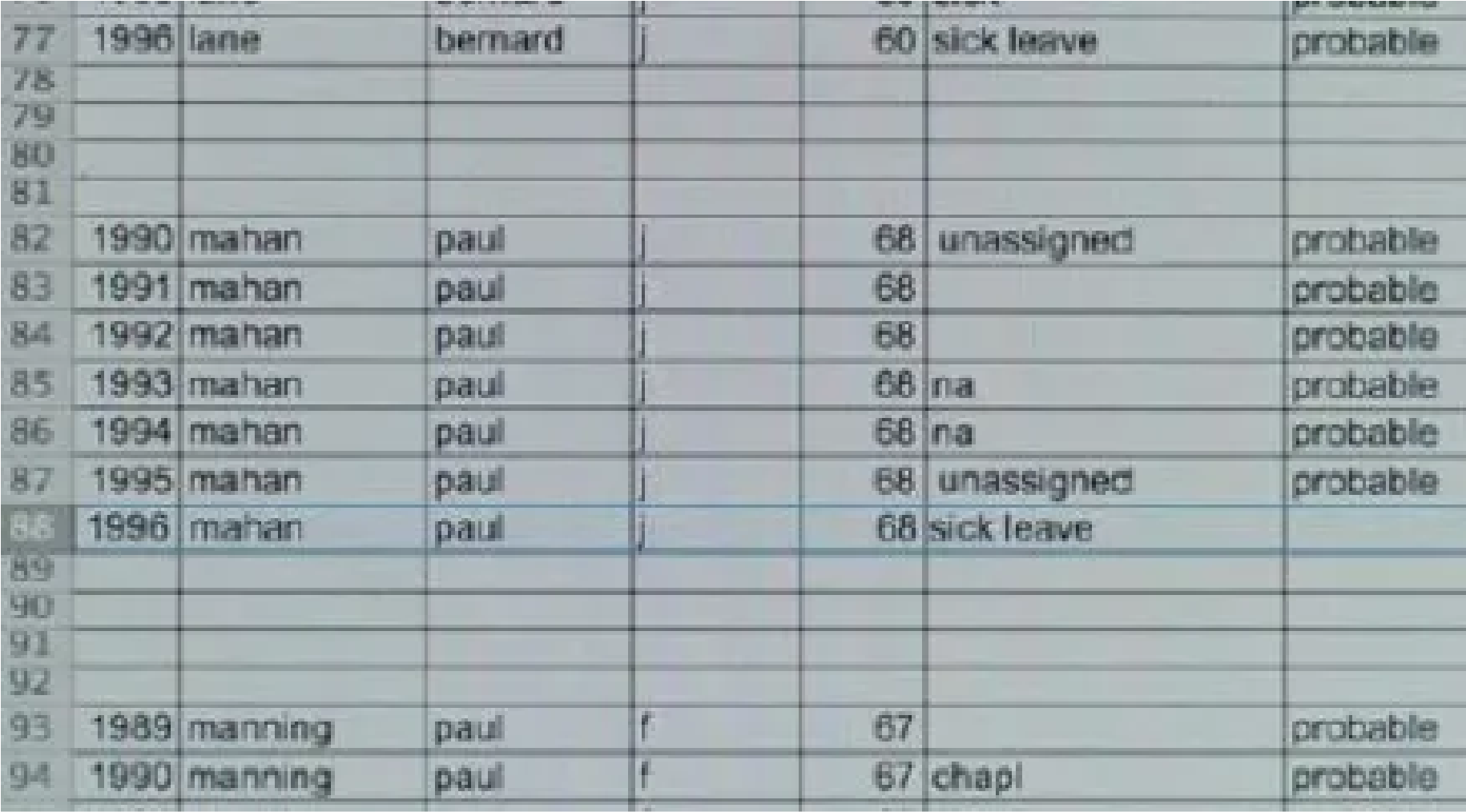

III. Track Something

You can also use summaries to track particular facts and pieces of evidence and to highlight patterns via repetition.

First, tracking something can create robust evidence that would not be obvious or compelling if presented solely via oral testimony, mainly when you track something that no one thought to lie about at the time.

Human resources records, such as the directories mentioned in the Spotlight example above, can be beneficial. Bonuses that continued and grew throughout a fraud scheme can help show that a defendant was more involved and knew more than she might claim. Also, payroll records can help show that a defendant was the only person who could have committed a particular crime.

Second, tracking something over time can reveal critical moments that corroborate witness testimony, show the defendant’s intent, or open up new investigative areas. In my fraud cases, I often break down the data by year and often by month, looking for those critical moments. Did the fraud peak sometime? If so, why? And if it never peaked, did the fraud continue despite red flags that should have been heeded? Did the scheme change at some point? If so, why?

For example, in one healthcare fraud case (United States v. Kolbusz), a doctor billed cosmetic light treatments as if they were medical procedures destroying large numbers of precancerous lesions. In 2006, one large insurance company started to catch on. In 2007, a peer warned the doctor that what he was doing looked like fraud. Data and documents showed that the doctor tried to keep the scam going. Suddenly, the total number of lesions he claimed to destroy each time dropped from a ridiculous number (120) to less unreasonable numbers (20–40), corroborating witness testimony about instructions that they had received. In context, this helped show criminal intent even more clearly.

From United States v. Kolbusz

Third, tracking disparate items in a single chart can help jurors see how the evidence fits together and save time for closing arguments. When evidence comes in at trial through multiple sources and out of chronological order, a simple timeline can help the jurors understand the materials better while you present the case. This can help them see the points you are trying to make rather than leaving them in confusion until closing arguments. For example, the timeline below was used in a Western District of Missouri case (United States v. Borders) involving multiple stolen and later recovered vehicles. Timelines like this one helped show what happened to a particular car, something that may have gotten lost otherwise.

From United States v. Borders

IV. Practice Pointers

Creating a good summary is like developing a good witness. It takes time and preparation, can be tedious and sometimes painful, but it can pay off.

Here are some pointers for creating good, effective summaries for trial:

Think of questions that data and documents might be able to answer.

Can the data corroborate a witness’s account of how the scheme worked? Can data from the defendant or someone else contradict the defendant’s statements or promises? Can the data tell you when a scheme peaked or collapsed, suggesting turning points useful to explain at trial? Are there flaws in the data or documents that can show the larger scheme (e.g., a defendant who is automatically billing for services not rendered will be revealed by occasional “mistakes,” such as billing for visits performed on patients who were dead or out of town)?

Build a database based on a targeted review of voluminous records.

When reviewing documents, do not count on finding a “smoking gun.” Cases can be made with the little details you must look for and aggregate. If you have boxes of documents to review, find a few things to track or add up and start recording the data. Create a template for the investigative team to use, test it out, track something, and collect the results in a table or spreadsheet.

Start counting, tracking, or contrasting something with draft charts.

Some helpful computer programs you can use are Microsoft Excel or Microsoft PowerPoint for charts, tables, or graphs, or Lexis TimeMap or PowerPoint for timelines (and there’s always paper!). If you need help setting up formulas, meet with a financial analyst and explain what you are trying to do (your office’s fiscal or accounting people generally should be familiar with Excel and might be able to help out as well). Your initial drafts may not work out or reveal helpful data that is unclear enough to use at trial. Step back and think of another way to look at the data from your database. Go back and track something else if necessary.

Make the charts clear and legible for a general audience.

Trials typically are not the place for complicated graphics based on complex formulas or for logarithmic scale. Make charts that convey a lot of information while being based on simple principles that a jury will be able to follow, and make sure the charts are legible to jurors looking at them from some distance. I generally make charts first in Microsoft Excel and then copy the chart over to PowerPoint, where I have more control over how the charts will look on the screen or when printed out.

Remember what the evidentiary rules allow and do not allow.

Lawyers can use three federal evidentiary rules to admit charts, which can differ in tone and use based on the particular rule being used. Charts admitted under Rule 1006 are substantive evidence and can go back to a jury for deliberations and generally should be non-argumentative. Charts allowed under Rule 611(a) or Rule 703 may be less neutral in presentation because they are viewed “more akin to argument than evidence.” Such charts cannot go back to a jury during deliberations.

Here’s a table to summarize the law regarding charts:

Show your work.

In a bank robbery case, simply saying that the defendant confessed is okay, but it is better first to give the details that help the jury figure that out. Similarly, it is OK to show a chart making your final point, but it is better to show your work and allow the jury to get there themselves. Before summarizing claims data or other records, I typically have a witness review specific examples. This can help establish the credibility of the summary and avoid confusing cross-examination.

Think about when you are going to admit your summaries at trial.

Data can corroborate insiders when describing a scheme, but consider flipping it around. If the summarized data goes in first, the jury might understand the scheme better and have a better context for the witnesses’ testimony. In healthcare fraud cases, presenting the defendant’s files highlighting implausible patterns may be a great way to start the trial. This can leave jurors with doubts about the defendant’s practice and sets up the testimony of witnesses whose testimony might otherwise be confusing or out of context.

Consider ways to ensure that your charts get admitted at trial.

Provide the underlying materials to defense counsel as part of discovery, and provide some charts to defense counsel as early as possible, even if they are in draft form. Consider providing the underlying spreadsheets with the formulas used to create the charts. This is by no means required but can avoid issues that might endanger admission at trial. Consider meeting with defense counsel to explain any methodologies ahead of trial. Also, consider filing motions with draft charts before trial to avoid last-minute problems.

Finally, do not wait until the trial to start thinking about what summaries might be helpful to at trial.

If you wait until trial to make your summary charts, you may never get to trial because you might never even get the case charged. Doing a summary chart during the investigative phase can open new leads and questions that can shape your case and even accelerate an investigation. Summary charts can corroborate witnesses and can help convince defendants to plead guilty. Embracing this approach early on can help you simplify and transform your cases.

The Stephen Lee Law legal blog covers various topics, including healthcare fraud defense, investigations, data analytics, and the federal anti-kickback statute.

For further insights into building a smoking gun or for legal guidance with healthcare fraud defense, please contact Stephen Lee Law.