Asian-Pacific American Heritage

Stephen began writing about Asian-American legal history after hearing about an 1850s murder case that resulted in an infamous opinion by the California Supreme Court. Stephen went through California archives to learn more about what happened in the case, and his article about the case has been used in law-school classes. In 2023, he wrote a monthlong series of articles about Asian-American legal history, some of which are below.

Stephen is currently the second vice president of the Asian American Bar Association of Greater Chicago. He also has been involved with many events, including starting a tradition of taking a photo of Asian-American attorneys who have served in the government at the National Asian Pacific American Bar Association’s annual convention.

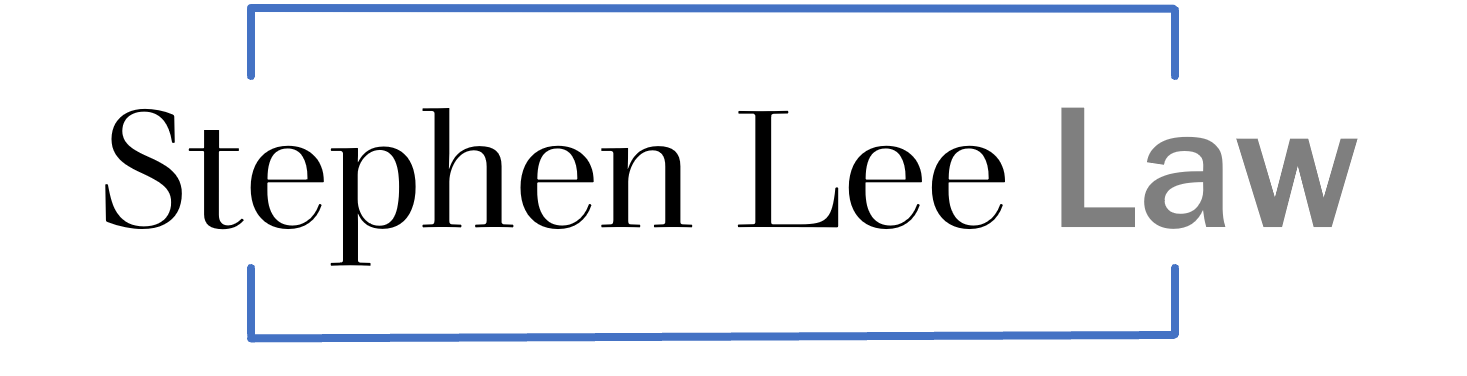

Loving v. Virginia: The JACL Argues for Interracial Marriage

When the United States Supreme Court held in 1967 that bans on interracial marriages were unconstitutional, a Japanese American civil rights group helped win this victory. In the 1960s, Virginia was one of 17 states that banned interracial marriages. Virginia’s ban declared that “all marriages between a white person and a colored person shall be absolutely void without any decree of divorce or other legal process,” and defined “white” as a person “who has no trace of whatsoever of any blood other than Caucasian.”

When the United States Supreme Court held in 1967 that bans on interracial marriages were unconstitutional, a Japanese American civil rights group helped win this victory.

In the 1960s, Virginia was one of 17 states that banned interracial marriages. Virginia’s ban declared that “all marriages between a white person and a colored person shall be void without any decree of divorce or other legal process” and defined “white” as a person “who has no trace of whatsoever of any blood other than Caucasian.”

The Landmark Case of Loving v. Virginia

Many groups supported Mildred and Richard Loving when they challenged Virginia’s law. The Japanese American Citizen League was the only one that filed an amicus brief and was given leave to argue before the Supreme Court.

During oral argument, Supreme Court justices had two questions for William Marutani, the JACL’s general counsel at the time.

William Marutani's Contribution to the Case

First, Marutani was asked if Virginia’s law would meet equal protection requirements if it banned all people of all races from intermarrying. He argued that the law would still be unconstitutional because it was, at heart, a “white supremacy” law, in addition to being one that was unworkable practically.

Second, Marutani was asked if Japan prohibited interracial marriages. He had already introduced himself as a Nisei – an American born and raised in the United States – and said he did not know. He said that his mother might have objected to his marrying a white person by “custom,” but the state should have no role in this area.

Later, Virginia’s attorney tried to defend the state’s ban as preventing only marriages between white and “colored” people. This argument was odd and probably just wrong since Virginia’s Supreme Court had upheld its ban to annul the marriage of a Chinese man and a white woman just a decade earlier in the Naim v. Naim case.

The Supreme Court's Historic Decision

Ultimately, the Supreme Court held Virginia’s ban unconstitutional for depriving the Lovings of liberty without due process of law. In a footnote, the Supreme Court said that it need not decide the equal protection argument that some justices had been thinking about because “we find the racial classifications in these statutes repugnant to the Fourteenth Amendment, even assuming an even-handed state purpose to protect the ‘integrity’ of all races.”

William Marutani's Legacy Beyond Loving v. Virginia

As for Marutani, he later became the first Asian American judge in Pennsylvania. He also served on a commission that studied the incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II and recommended that the U.S. government issue a formal apology and make reparations payments, which happened in the 1980s.

Stephen Chahn Lee has written about Asian American legal history throughout his time as a lawyer, illuminating the pivotal legal battles fought by Asian Pacific Americans and their role in shaping the rights and freedoms we uphold today. This article was one of a series that Stephen wrote in 2023 and that grew out of an event that Stephen organized for the United States District Court of the Northern District of Illinois, the Federal Bar Association Chicago Chapter, the Asian American Bar Association of Greater Chicago, and other bar associations.

For further insights into Loving v. Virginia or legal guidance with healthcare fraud defense, please contact Stephen Lee Law.

Sources

Muto, David. "An Unsung Hero in the Story of Interracial Marriage." New Yorker, November 17, 2016. Read here.

"Oral Argument Transcript of Loving v. Virginia." Access online.

I would like to give special thanks to Nancy Marutani for providing a copy of the Japanese American Citizens League's amicus brief and for sharing insights about her father, William Marutani.

Before Brown: The Lum Family's Fight for School Equality

Decades before Brown v. Board of Education, the Lum family challenged segregation in public schools on behalf of their daughter Martha. There are many amazing immigrant mothers out there, but Katherine Lum stands out and should be better known.

Decades before Brown v. Board of Education, the Lum family challenged segregation in public schools on behalf of their daughter Martha. There are many amazing immigrant mothers out there, but Katherine Lum stands out and should be better known.

A Family’s Fight Against Segregation Before Brown v. Board of Education

Martha had been going to school with white children for years, and she was a straight-A student. But on her first day of high school, she was told that she, her sister, and two other girls had to leave. Mississippi’s constitution at the time required separate schools for “children of the white and colored races,” and the school policy treated Chinese as “colored.”

There were not many Asian Americans in the South in the 1920s, but there were a few hundred Chinese in Mississippi along with two Hindus and one Filipino, according to 1920 census data. Katherine Lum had come to be a servant for a Chinese merchant. Jeu Gong Lum had entered the country illegally and had come to the South for work. They met, married, and had their children in Mississippi.

Other families accepted the school’s policy, but Katherine Lum would not back down. She and her husband convinced former Mississippi Governor Earl Brewer to bring a case.

The Lum Legal Battle and Its Aftermath

“The state collects from all for the benefit of all. Martha Lum is one of the state’s children and is entitled to the enjoyment of the privilege of the public school system without regard to her race,” Brewer argued before the Mississippi Supreme Court in 1925.

The Lums lost their case – the Mississippi Supreme Court ruled unanimously in favor of school segregation. They then appealed to the United States Supreme Court, but a different lawyer handled the appeal. His brief was so bad that one of the justices asked about getting the Lums a better counsel, but this lawyer stayed on and even waived oral argument.

The United States Supreme Court unanimously affirmed the Mississippi Supreme Court’s decision in 1927, letting stand racial segregation within public schools until Brown v. Board of Education in 1954.

As for Martha, her sister and her younger brother, Katherine Lum sent them to a relative in Michigan, where they were able to attend public schools with other immigrant children, albeit in very difficult family circumstances. Katherine then found a white school in Arkansas that agreed to take her children and moved the family there. Martha and her sister graduated from high school in 1933.

Stephen Chahn Lee has written about Asian American legal history throughout his time as a lawyer, illuminating the pivotal legal battles fought by Asian Pacific Americans and their role in shaping the rights and freedoms we uphold today. This article was one of a series that Stephen wrote in 2023 and that grew out of an event that Stephen organized for the United States District Court of the Northern District of Illinois, the Federal Bar Association Chicago Chapter, the Asian American Bar Association of Greater Chicago, and other bar associations.

For further insights into the story of the Lum family’s fight for school equality or for legal guidance with healthcare fraud defense, please contact Stephen Lee Law.

Source Acknowledgement

This article draws extensively from Adrienne Berard's insightful book, Water Tossing Boulders: How A Family of Chinese Immigrants Led the First Fight to Desegregate Schools in the Jim Crow South. Special thanks to Adrienne Berard for her invaluable book and assistance.

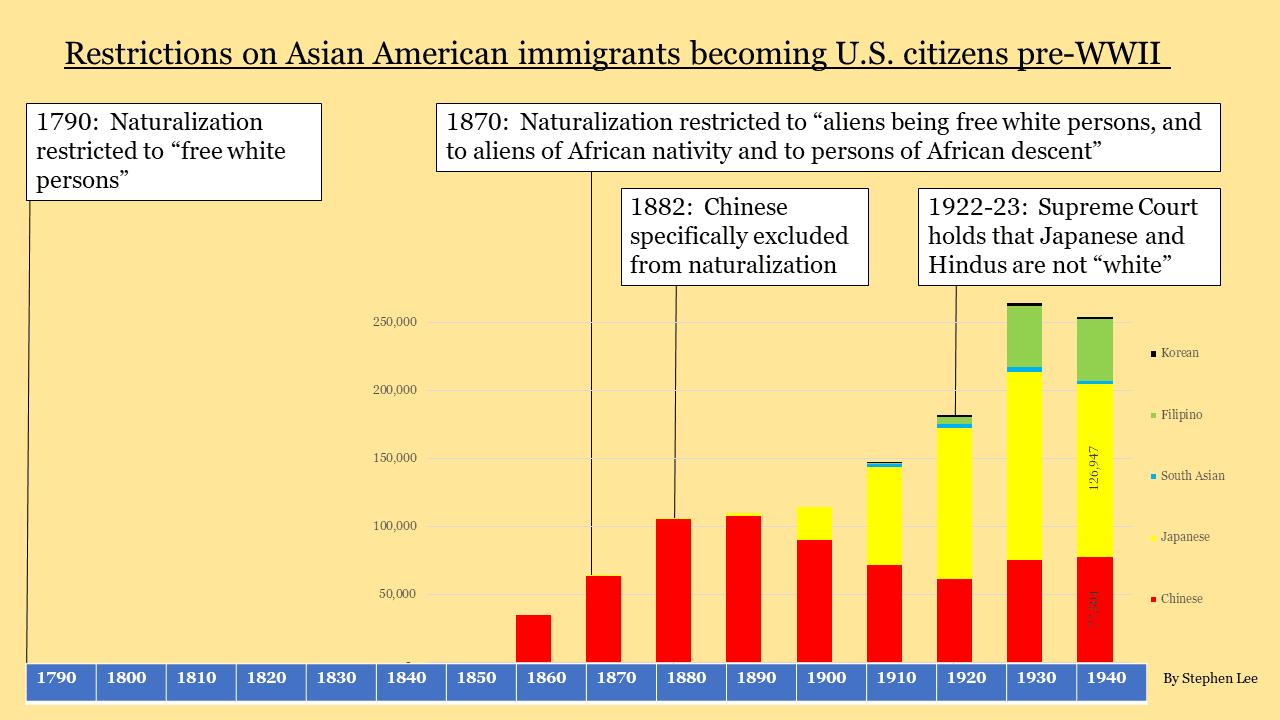

When Citizenship Depended on Race: Discussing Pre-World War II Restrictions

When citizenship depended on race, Asian American immigrants faced numerous barriers to becoming U.S. citizens before World War II. This introduction offers a visual journey through the history of these racial restrictions. Initially created for a webinar hosted by the Asian American Bar Association of Greater Chicago, the Federal Bar Association, and the National Asian Pacific American Bar Association, I am now broadening the reach of this important narrative.

When citizenship depended on race, Asian American immigrants faced numerous barriers to becoming U.S. citizens before World War II. This introduction offers a visual journey through the history of these racial restrictions. Initially created for a webinar hosted by the Asian American Bar Association of Greater Chicago, the Federal Bar Association, and the National Asian Pacific American Bar Association, I am now broadening the reach of this critical narrative.

Exploring a Time When Citizenship Depended on Race

First, the naturalization law of 1790 restricted U.S. citizenship to “free white persons.” At that time, the U.S. population was 80 percent white and 20 percent black (18 percent enslaved person, 2 percent free).

Second, in the 1800s, Chinese immigrants started seeking U.S. citizenship, and some did become citizens thanks to judges who read the naturalization law’s restriction very narrowly. This helped contribute to a legislative backlash – an 1882 law specifically excluded the Chinese from naturalization and led to a slight decline in the Chinese American population.

Third, as other Asian immigrants came from different counties, they also sought citizenship, especially as some states required U.S. citizenship to own property and work in some professions. In 1922 and 1923, the U.S. Supreme Court held that Japanese and Hindu people were not “white” and thus were not eligible for citizenship.

Fourth, these restrictions had real consequences for Asian Americans, professionally and personally. This has significant implications for families since immigrants’ children were U.S. citizens if born in the United States, but the immigrants could not become citizens.

Finally, the United States started easing these restrictions in the 1940s and 1950s, in part because of international relations during and after World War II. In 1952, race was finally stricken as a requirement for citizenship. Further changes to immigration law in the 1960s led to a huge growth in the Asian American population.

Stephen Chahn Lee has written about Asian American legal history throughout his time as a lawyer, illuminating the pivotal legal battles fought by Asian Pacific Americans and their role in shaping the rights and freedoms we uphold today. This article was one of a series that Stephen wrote in 2023 and that grew out of an event that Stephen organized for the United States District Court of the Northern District of Illinois, the Federal Bar Association Chicago Chapter, the Asian American Bar Association of Greater Chicago, and other bar associations.

For further insights into pre-World War II American citizenship restrictions or for legal guidance with healthcare fraud defense, please get in touch with Stephen Lee Law.

Sources

Gibson, Campbell, and Kay Jung. Historical Census Statistics on Population Totals by Race, 1790 to 1990, and by Hispanic Origin, 1970 to 1990, for the United States, Regions, Divisions, and States. U.S. Census.