Asian-Pacific American Heritage

Stephen began writing about Asian-American legal history after hearing about an 1850s murder case that resulted in an infamous opinion by the California Supreme Court. Stephen went through California archives to learn more about what happened in the case, and his article about the case has been used in law-school classes. In 2023, he wrote a monthlong series of articles about Asian-American legal history, some of which are below.

Stephen is currently the second vice president of the Asian American Bar Association of Greater Chicago. He also has been involved with many events, including starting a tradition of taking a photo of Asian-American attorneys who have served in the government at the National Asian Pacific American Bar Association’s annual convention.

Sau Ung Loo Chan: A Pioneering Asian-American Lawyer

I have researched a lot of amazing stories of Asian-American legal history, but this one may be my favorite. I discovered it in a footnote and wanted to know more. Sau Ung Loo Chan was one of the first Asian Americans to graduate from Yale Law School, and she was also one of the first women to do so. And she brought her training and drive to winning perhaps the most important case of her life – proving that her husband was an American.

I have researched a lot of amazing stories of Asian-American legal history, but this one may be my favorite. I discovered it in a footnote and wanted to know more.

Sau Ung Loo Chan first had to prove her U.S. citizenship during law school in the 1920s. She was one of the first Asian Americans to attend Yale Law School and one of the first women to do so.

On her way back from a student trip to Europe, she was refused re-entry and was threatened with detainment. “After having finished one year at Yale, I knew just enough law to scream ‘habeas corpus’ at the immigration officials, and they finally let me in,” she later recalled.

Years later, she used her training and drive to win perhaps the most important case of her life—proving that her husband was an American.

Sau Ung Loo Chan’s Early Life and Legal Challenges

The case was rooted in family tragedy and drama long before she met her husband, Chan Hin Cheung, and the complicated racial restrictions in naturalization law in the early 20th century.

Chan was born in San Francisco in 1906, but the San Francisco earthquake ruined his father’s health and finances, so the family went to China in 1907, and his father died soon afterward.

Chan grew up in China but wanted to go to the United States to study at Phillips Academy. His mother was worried he would not return to her, so she let him believe he would be an international student in the United States, not a native-born citizen returning home.

Soon, upon arrival, he began to suspect that he had been born in the United States. But he did not know until 1927 when he confronted his mother in China, and she admitted the truth.

He tried to clear this up with U.S. immigration authorities in 1928. Still, they were suspicious and concluded that he was an “impostor seeking a return certificate through fraud and misrepresentation.”

The Struggle for Citizenship

Clearing up his citizenship became a priority after he met Sau Ung Loo, a Chinese American born in Hawaii and attending Yale Law School. Marriage could have serious legal consequences for her – U.S. law at the time stripped American women of their citizenship if they married a non-citizen. This law reportedly had been designed to punish rich American women who married European men with titles (think Downton Abbey). Still, the law severely impacted Asian-American women who married Asian-American immigrant men.

They decided to go to China together to find evidence of his birth, but they ran into trouble. While he had been in the United States, Chan’s mother had picked out a Chinese girl for her son to marry, and she refused to help prove her son’s citizenship and threatened to never speak with him again unless he broke off the engagement with Sau Ung.

Despite all the legal and familial consequences, Chan Hin Cheung and Sau Ung Loo married in Hong Kong in 1929. But they did not give up hope.

“You knowing how thoroughly Americanized my wife is and the value she places upon her U.S. citizenship—we being absolutely alike in this respect—I need not stress the importance of our having our status definitely cleared,” Chan wrote in a 1931 letter.

A Family's Second Fight for Citizenship

The second time was more challenging.

Her husband (first name Hin, family name Chan) was born in the United States. Stidid did not know that fact until he was a teenager, so he had inadvertently given false information to immigration authorities when he first entered the United States in 1922. Clearing this up would be difficult, especially since her mother-in-law refused to help Chan prove his ownership unless he renounced Sau Ung.

Sau Ung and Hin got married in 1929 despite the familial and legal consequences - Sau Ung lost her citizenship by marrying a man whom the U.S. viewed as an ineligible alien to become a citizen (U.S. law at the time prevented Asian immigrants from becoming citizens because they were not “white” and stripped American women’s citizenship if they married someone who was not a citizen). She managed to get her citizenship restored in 1934, but that still left the citizenship of her husband and that of their daughter unclear (born in 1932 in Hong Kong).

The Legal Battle for Chan Hin Cheung's Citizenship

Proving her husband’s citizenship took more than a decade.

First, she had to convince Chan’s mother to cooperate. “Year to year, we tried to get reconciled with my mother-in-law, but she refused to have anything to do with us,” she later explained. Finally, in 1937, Chan’s mother signed the affidavit she had refused to sign eight years earlier.

Second, she had many connections due to her family’s status in Hawaii (her father was a court interpreter, and she had graduated from Punahou School), and she worked there, even managing to meet directly with a top immigration official in San Francisco. As a result of all this, her husband was released on bond while his case was pending, rather than being detained like many other Asian Americans.

Third, she reached out to people in California and China who could corroborate parts of her husband’s family history and a U.S. official in Panama who had known her in Hong Kong and managed to clear up one inconsistency.

Fourth, she tracked down records showing that her husband was the same boy born in San Francisco in 1906, including a birth certificate that had been assumed to have been destroyed, 11 years of school records, and estate records.

Finally, she testified in an immigration hearing with her husband. At the end, she was asked if she had anything that she wanted to say:

“I want to say that he was born in San Francisco; otherwise, we would have given up the claim long ago. We had to wait year after year to get help from his mother, and she refused for a long time. My husband felt that it was rather hopeless. That is all I have to say.”

Thanks to all her work, immigration officials agreed that there was a “substantial body of evidence” that Chan was born in the United States and was admitted back to the United States as a U.S. citizen.

Sau Ung Loo Chan's Legacy

Not only did Sau Ung win the case, but she impressed immigration authorities so much that they offered her a job! She worked briefly for the government and then began a long and distinguished legal career in Hawaii. In 1994, the Hawaii State Bar Association recognized her legal career, and in 1995, a Chinese organization named her “Model Chinese Mother of the Year.” She passed away in 2002.

Stephen Chahn Lee has written about Asian American legal history throughout his time as a lawyer, illuminating the pivotal legal battles fought by Asian Pacific Americans and their role in shaping the rights and freedoms we uphold today. This article was one of a series that Stephen wrote in 2023 and that grew out of an event that Stephen organized for the United States District Court of the Northern District of Illinois, the Federal Bar Association Chicago Chapter, the Asian American Bar Association of Greater Chicago, and other bar associations.

For further insights into the story of Sau Ung Loo Chan or for legal guidance with healthcare fraud defense, please contact Stephen Lee Law.

Sources

Damon, Annabel. "Local Attorney Makes Hobby of Immigration Law." Honolulu Advertiser, September 13, 1949.

Fruto, Ligaya. "Small Estates Are Serious Problem to Estate Lawyer." Honolulu Star-Bulletin, January 31, 1960.

Hacker, Meg. "When Saying ‘I Do’ Meant Giving Up Your U.S. Citizenship." Access online.

Matsuda, Mari J., editor. Called from Within: Early Women Lawyers of Hawaii. (Includes a chapter on Sau Ung Loo Chan.)

Volpp, Leti. "Divesting Citizenship: On Asian American History and the Loss of Citizenship Through Marriage." 53 UCLA Law Review 405 (2005).

Acknowledgements: Special thanks to Jane Park for her assistance with Sau Ung Loo Chan's oral history at Yale Law School, Caroline Kness for organizing archival materials, and the helpful archivist at the National Archives for providing the case file of Sau Ung Loo Chan's husband.

Appreciation is also extended to Phillips Academy for making its historical yearbooks available online, which provided valuable insights into Chan Hin Cheung's background.

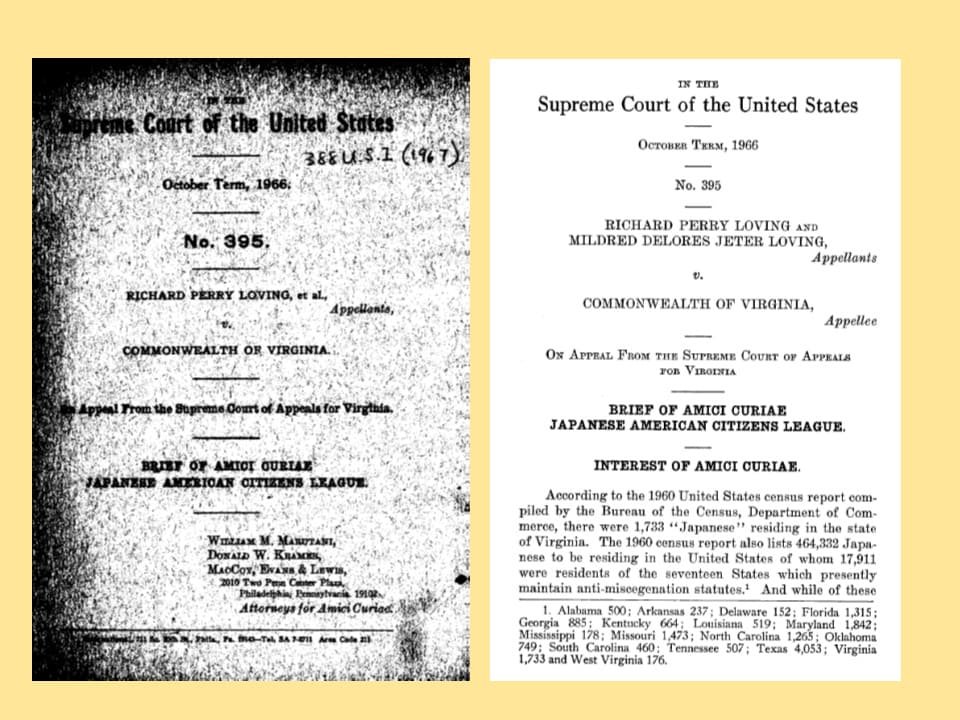

Loving v. Virginia: The JACL Argues for Interracial Marriage

When the United States Supreme Court held in 1967 that bans on interracial marriages were unconstitutional, a Japanese American civil rights group helped win this victory. In the 1960s, Virginia was one of 17 states that banned interracial marriages. Virginia’s ban declared that “all marriages between a white person and a colored person shall be absolutely void without any decree of divorce or other legal process,” and defined “white” as a person “who has no trace of whatsoever of any blood other than Caucasian.”

When the United States Supreme Court held in 1967 that bans on interracial marriages were unconstitutional, a Japanese American civil rights group helped win this victory.

In the 1960s, Virginia was one of 17 states that banned interracial marriages. Virginia’s ban declared that “all marriages between a white person and a colored person shall be void without any decree of divorce or other legal process” and defined “white” as a person “who has no trace of whatsoever of any blood other than Caucasian.”

The Landmark Case of Loving v. Virginia

Many groups supported Mildred and Richard Loving when they challenged Virginia’s law. The Japanese American Citizen League was the only one that filed an amicus brief and was given leave to argue before the Supreme Court.

During oral argument, Supreme Court justices had two questions for William Marutani, the JACL’s general counsel at the time.

William Marutani's Contribution to the Case

First, Marutani was asked if Virginia’s law would meet equal protection requirements if it banned all people of all races from intermarrying. He argued that the law would still be unconstitutional because it was, at heart, a “white supremacy” law, in addition to being one that was unworkable practically.

Second, Marutani was asked if Japan prohibited interracial marriages. He had already introduced himself as a Nisei – an American born and raised in the United States – and said he did not know. He said that his mother might have objected to his marrying a white person by “custom,” but the state should have no role in this area.

Later, Virginia’s attorney tried to defend the state’s ban as preventing only marriages between white and “colored” people. This argument was odd and probably just wrong since Virginia’s Supreme Court had upheld its ban to annul the marriage of a Chinese man and a white woman just a decade earlier in the Naim v. Naim case.

The Supreme Court's Historic Decision

Ultimately, the Supreme Court held Virginia’s ban unconstitutional for depriving the Lovings of liberty without due process of law. In a footnote, the Supreme Court said that it need not decide the equal protection argument that some justices had been thinking about because “we find the racial classifications in these statutes repugnant to the Fourteenth Amendment, even assuming an even-handed state purpose to protect the ‘integrity’ of all races.”

William Marutani's Legacy Beyond Loving v. Virginia

As for Marutani, he later became the first Asian American judge in Pennsylvania. He also served on a commission that studied the incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II and recommended that the U.S. government issue a formal apology and make reparations payments, which happened in the 1980s.

Stephen Chahn Lee has written about Asian American legal history throughout his time as a lawyer, illuminating the pivotal legal battles fought by Asian Pacific Americans and their role in shaping the rights and freedoms we uphold today. This article was one of a series that Stephen wrote in 2023 and that grew out of an event that Stephen organized for the United States District Court of the Northern District of Illinois, the Federal Bar Association Chicago Chapter, the Asian American Bar Association of Greater Chicago, and other bar associations.

For further insights into Loving v. Virginia or legal guidance with healthcare fraud defense, please contact Stephen Lee Law.

Sources

Muto, David. "An Unsung Hero in the Story of Interracial Marriage." New Yorker, November 17, 2016. Read here.

"Oral Argument Transcript of Loving v. Virginia." Access online.

I would like to give special thanks to Nancy Marutani for providing a copy of the Japanese American Citizens League's amicus brief and for sharing insights about her father, William Marutani.

Before Brown: The Lum Family's Fight for School Equality

Decades before Brown v. Board of Education, the Lum family challenged segregation in public schools on behalf of their daughter Martha. There are many amazing immigrant mothers out there, but Katherine Lum stands out and should be better known.

Decades before Brown v. Board of Education, the Lum family challenged segregation in public schools on behalf of their daughter Martha. There are many amazing immigrant mothers out there, but Katherine Lum stands out and should be better known.

A Family’s Fight Against Segregation Before Brown v. Board of Education

Martha had been going to school with white children for years, and she was a straight-A student. But on her first day of high school, she was told that she, her sister, and two other girls had to leave. Mississippi’s constitution at the time required separate schools for “children of the white and colored races,” and the school policy treated Chinese as “colored.”

There were not many Asian Americans in the South in the 1920s, but there were a few hundred Chinese in Mississippi along with two Hindus and one Filipino, according to 1920 census data. Katherine Lum had come to be a servant for a Chinese merchant. Jeu Gong Lum had entered the country illegally and had come to the South for work. They met, married, and had their children in Mississippi.

Other families accepted the school’s policy, but Katherine Lum would not back down. She and her husband convinced former Mississippi Governor Earl Brewer to bring a case.

The Lum Legal Battle and Its Aftermath

“The state collects from all for the benefit of all. Martha Lum is one of the state’s children and is entitled to the enjoyment of the privilege of the public school system without regard to her race,” Brewer argued before the Mississippi Supreme Court in 1925.

The Lums lost their case – the Mississippi Supreme Court ruled unanimously in favor of school segregation. They then appealed to the United States Supreme Court, but a different lawyer handled the appeal. His brief was so bad that one of the justices asked about getting the Lums a better counsel, but this lawyer stayed on and even waived oral argument.

The United States Supreme Court unanimously affirmed the Mississippi Supreme Court’s decision in 1927, letting stand racial segregation within public schools until Brown v. Board of Education in 1954.

As for Martha, her sister and her younger brother, Katherine Lum sent them to a relative in Michigan, where they were able to attend public schools with other immigrant children, albeit in very difficult family circumstances. Katherine then found a white school in Arkansas that agreed to take her children and moved the family there. Martha and her sister graduated from high school in 1933.

Stephen Chahn Lee has written about Asian American legal history throughout his time as a lawyer, illuminating the pivotal legal battles fought by Asian Pacific Americans and their role in shaping the rights and freedoms we uphold today. This article was one of a series that Stephen wrote in 2023 and that grew out of an event that Stephen organized for the United States District Court of the Northern District of Illinois, the Federal Bar Association Chicago Chapter, the Asian American Bar Association of Greater Chicago, and other bar associations.

For further insights into the story of the Lum family’s fight for school equality or for legal guidance with healthcare fraud defense, please contact Stephen Lee Law.

Source Acknowledgement

This article draws extensively from Adrienne Berard's insightful book, Water Tossing Boulders: How A Family of Chinese Immigrants Led the First Fight to Desegregate Schools in the Jim Crow South. Special thanks to Adrienne Berard for her invaluable book and assistance.

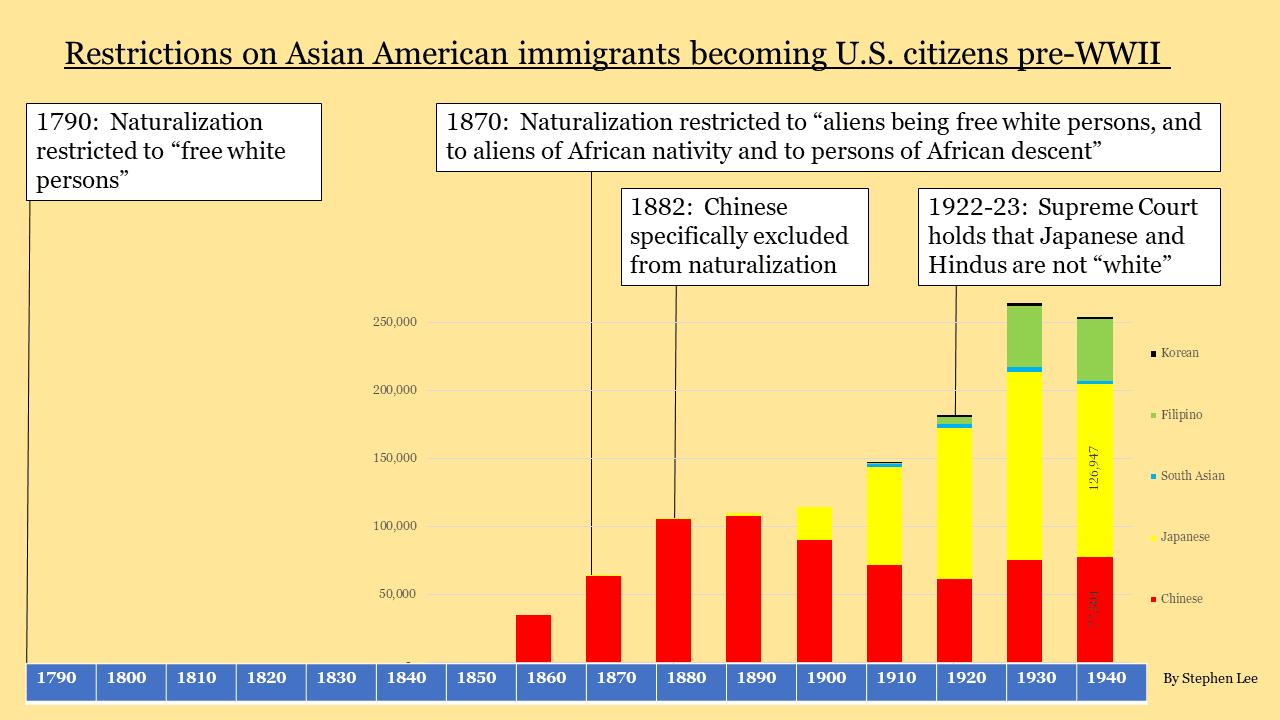

When Citizenship Depended on Race: Discussing Pre-World War II Restrictions

When citizenship depended on race, Asian American immigrants faced numerous barriers to becoming U.S. citizens before World War II. This introduction offers a visual journey through the history of these racial restrictions. Initially created for a webinar hosted by the Asian American Bar Association of Greater Chicago, the Federal Bar Association, and the National Asian Pacific American Bar Association, I am now broadening the reach of this important narrative.

When citizenship depended on race, Asian American immigrants faced numerous barriers to becoming U.S. citizens before World War II. This introduction offers a visual journey through the history of these racial restrictions. Initially created for a webinar hosted by the Asian American Bar Association of Greater Chicago, the Federal Bar Association, and the National Asian Pacific American Bar Association, I am now broadening the reach of this critical narrative.

Exploring a Time When Citizenship Depended on Race

First, the naturalization law of 1790 restricted U.S. citizenship to “free white persons.” At that time, the U.S. population was 80 percent white and 20 percent black (18 percent enslaved person, 2 percent free).

Second, in the 1800s, Chinese immigrants started seeking U.S. citizenship, and some did become citizens thanks to judges who read the naturalization law’s restriction very narrowly. This helped contribute to a legislative backlash – an 1882 law specifically excluded the Chinese from naturalization and led to a slight decline in the Chinese American population.

Third, as other Asian immigrants came from different counties, they also sought citizenship, especially as some states required U.S. citizenship to own property and work in some professions. In 1922 and 1923, the U.S. Supreme Court held that Japanese and Hindu people were not “white” and thus were not eligible for citizenship.

Fourth, these restrictions had real consequences for Asian Americans, professionally and personally. This has significant implications for families since immigrants’ children were U.S. citizens if born in the United States, but the immigrants could not become citizens.

Finally, the United States started easing these restrictions in the 1940s and 1950s, in part because of international relations during and after World War II. In 1952, race was finally stricken as a requirement for citizenship. Further changes to immigration law in the 1960s led to a huge growth in the Asian American population.

Stephen Chahn Lee has written about Asian American legal history throughout his time as a lawyer, illuminating the pivotal legal battles fought by Asian Pacific Americans and their role in shaping the rights and freedoms we uphold today. This article was one of a series that Stephen wrote in 2023 and that grew out of an event that Stephen organized for the United States District Court of the Northern District of Illinois, the Federal Bar Association Chicago Chapter, the Asian American Bar Association of Greater Chicago, and other bar associations.

For further insights into pre-World War II American citizenship restrictions or for legal guidance with healthcare fraud defense, please get in touch with Stephen Lee Law.

Sources

Gibson, Campbell, and Kay Jung. Historical Census Statistics on Population Totals by Race, 1790 to 1990, and by Hispanic Origin, 1970 to 1990, for the United States, Regions, Divisions, and States. U.S. Census.